Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

Lorenzo de' Medici—a leading statesman, the uncrowned ruler of Florence during its golden age, a true Renaissance man known to history as Il Magnifico (the Magnificent). Lorenzo was not only the foremost patron of his day but also a renowned poet, equally adept at composing philosophical verses and obscene rhymes to be sung at Carnival. He befriended the greatest artists and writers of the time—Leonardo, Botticelli, Poliziano, and, especially, Michelangelo, whom he discovered as a young boy and invited to live at his palace—and, in the process, turned Florence into the cultural capital of Europe.

Though Lorenzo's grandfather Cosimo had converted the vast wealth of the family bank into political power, Lorenzo's position was precarious. Bitter rivalries among the leading Florentine families and competition among the squabbling Italian states meant that Lorenzo's life was under constant threat. Those who plotted his death included a pope, a king, and a duke, but Lorenzo used his legendary charm and diplomatic skill—as well as occasional acts of violence—to navigate the murderous labyrinth of Italian politics.

Florence in the age of Lorenzo was a city of contrasts, of unparalleled artistic brilliance and unimaginable squalor in the city's crowded tenements; of both pagan excess and the fire-and-brimstone sermons of the Dominican preacher Savonarola. Florence gave birth to both the otherworldly perfection of Botticelli's Primavera and the gritty realism of Machiavelli's The Prince. Nowhere was this world of contrasts more perfectly embodied than in the life and character of the man who ruled this most fascinating city.

Excerpt

I. THE ROAD FROM CAREGGI

“[I]t is necessary now for you to be a man and not a boy; be so in words, deeds and manners.”

—PIERO DE’ MEDICI TO LORENZO, MAY 11, 1465

LATE ON THE MORNING OF AUGUST 27, 1466, A SMALL group of horsemen left the Medici villa at Careggi and turned onto the road to Florence. It was a journey of three miles from the villa to the city walls along a meandering path that descended through the hills that rise above Florence to the north. Dark cypresses and hedges of fragrant laurel lined the road, providing welcome shade in the summer heat. Through the trees the riders could catch from time to time a glimpse of the Arno River flashing silver in the sun.

On any other day this would have been a relaxing journey of an hour or so, the heavy August air encouraging a leisurely pace, the beauties of the Tuscan countryside inspiring laughter and conversation among the young men. “There is in my opinion no region more sweet or pleasing in Italy or in any other part of Europe than that wherein Florence is placed,” wrote a Venetian visitor, “for Florence is situated in a plain surrounded on all sides by hills and mountains…. And the hills are fertile, cultivated, pleasant, all bearing beautiful and sumptuous palaces built at great expense and boasting all manner of fine features: gardens, woods, fountains, fish ponds, pools and much else besides, with views that resemble paintings.”

But today, the mood was somber. The men peered nervously from side to side, fingering the pommels of their swords. Gnarled olive trees, ancient and silver-leaved, hugged terraces cut into the slopes, and parallel rows of vines glistening with purple grapes gave the hills a tidy geometry worthy of a fresco by Fra Angelico.

Taking the lead was a young man who rode with the easy grace of a born horseman. His appearance was distinctive, though not at first glance particularly attractive. Above an athletic frame, bony and long-limbed, was a rough-hewn face. His nose, which was flattened and turned to the side as if it had once been broken, gave him something of the look of a street brawler, and the prominent jaw that caused his lower lip to jut out pugnaciously did nothing to soften this impression. Beneath heavy brows peered black, piercing eyes more suggestive of animal cunning than refined intelligence. Dark hair, parted in the middle, hung down to his shoulders, providing a stern frame to the irregular features. Even a close friend, Niccolò Valori, was forced to admit that “nature had been a step-mother to him with regard to his personal appearance. [N]onetheless,” continued Valori, “when it came to the inner man she truly acted as a kindly mother…. [A]lthough his face was not handsome it was full of such dignity as to command respect.”*

This homely face belonged to Lorenzo, the seventeen-year-old son and heir of Piero de’ Medici. Since the death of Lorenzo’s grandfather Cosimo, two years earlier, Piero had taken over the far-flung Medici banking empire, a position that made him one of the richest men in Europe. But it was not wealth alone that made the Medici name famous throughout Europe. The Medici, though they possessed no titles, were regarded by those unfamiliar with the intricacies of local politics as kings in all but name of the independent Florentine Republic, which, though small compared with the great states of Europe, dazzled the civilized world through the brilliance of her art and the vitality of her intellectual life.† Not many generations removed from their peasant origins, the Medici spent lavishly on beautifying their city in the expectation that at least some of its glamour would rub off on its first family.

It was Cosimo who had parlayed his apparently inexhaustible fortune into a position of unprecedented authority in the state. On his tombstone in the family church of San Lorenzo were the words Pater Patriae (“Father of His Country”), bestowed on him by a grateful public for his wise stewardship and generous patronage of the city’s civic and religious institutions. Cosimo had dominated the councils of government through the force of his personality and his willingness to open his own coffers when the state was short of cash. Florentines, like modern-day Americans, had a healthy respect for money and seemed to feel that those who showed a talent for amassing it must possess other, less visible virtues. Cosimo rarely held high political office, happy to let others enjoy the pomp of life in the Palazzo della Signoria as long as important decisions were left in his hands.* For a time the gratitude Florentines felt toward Cosimo earned for his son Piero the allegiance of a majority of the citizens, and, until recent troubles, it had been generally assumed that this crucial position as the leading figure in the reggimento—the regime that really ran Florence, whoever temporarily occupied the government palace—would one day pass to the young man now guiding his small band along the road to Florence.

On this August morning, however, the fate of the Medici and their government seemed to teeter on a knife’s edge. The ancient constitution of the republic, in which the governing of the state had been shared widely among the city’s wealthy and middle-class citizens, had been undermined by this single family’s rise to prominence.† The heavy-handed tactics they used to win and to wield power had stirred up resentment as once proud families saw themselves reduced to little more than servants of the Medici court.

But now a group of rich and influential men saw an opportunity to strike back. The various factions that normally made Florentine politics a lively affair had been secretly arming themselves for months. Rumors of foreign armies on the march—a different one for each side in the contest—increased the general paranoia until it seemed as if the smallest incident might touch off a general conflagration.

On one side were the Medici loyalists, the Party of the Plain (named for the site of the Medici palace on low-lying land on the north bank of the Arno), who favored the current system, which they claimed had brought decades of peace and prosperity. On the other was the Party of the Hill, centered on Luca Pitti’s palace on the high ground to the south, who pointed out that Medici ascendance had been purchased at the expense of the people’s traditional liberty. The most visible figures in the rebellion were former members of Cosimo’s inner circle whose democratic zeal, not much in evidence in recent years, was rekindled by the humiliating prospect of having to take orders from his son. Few of them, in fact, had sterling reformist credentials. Most had connived with Cosimo in his systematic undermining of republican institutions, but now they adopted as their own the slogan “Popolo e Libertà!” (the “People and Liberty!”).

Discontent with the despotic tendencies of the government was not the only factor precipitating the current crisis. The perceived weakness of the fifty-year-old Piero contributed to a general sense that the regime was not only corrupt but, perhaps even worse, adrift. Even before Cosimo’s death in 1464 the influential Agnolo Acciaiuoli, now one of the leaders of the Hill, complained that Cosimo and Piero had become “cold men, whom illness and old age have reduced to such cowardice that they avoid anything that might cause them trouble or worry.” The citizens of Florence, said the uncharitable Niccolò Machiavelli some years later, “did not have much confidence in [Cosimo’s] son Piero, for notwithstanding that he was a good man, nonetheless, they judged that…he was too infirm and new in the state.”

Even many of Piero’s supporters shared that gloomy assessment. From his youth, Piero (known to history as il Gottoso, the Gouty) had been plagued by the family ailment that rendered him for long periods a virtual prisoner in his own house. It was a disease that affected not only his body but his temper. The architect Filarete wrote in his biographical sketch of the Medici leader, “those who have [gout] are usually rather acid and sharp in their manner,” but that while “few can bear its pains…[Piero] bears it with all the patience he can.” Piero also lacked his father’s common touch, the earthy humor that endeared Cosimo to the city’s humbler elements. (Once when a petitioner, hoping to reform the sagging morals of the city, begged Cosimo to pass a law prohibiting priests from gambling, the practical Cosimo replied, “First stop them from using loaded dice.” ) Piero, by contrast, was an aesthete and connoisseur who liked nothing better than to retire to his study, where he could gaze at his fine collection of antique busts, ancient manuscripts, and rare gemstones.

Citizens complained that policy was hatched in the privacy of the Medici palace on the Via Larga, rather than in open debate at the Palace of the Priors, as the sickly Piero was often forced to meet with his trusted lieutenants over dinner in his house or in his bedchamber. Such a reserved and quiet man was unlikely to appeal to the pragmatic merchants of Florence, who approached politics in much the same lively spirit as they entered the city’s marketplaces, eager to buy and sell, to argue and cajole, to win an advantage if possible but in any case to strike deals and shake hands at the conclusion of a bargain hard driven but mutually beneficial. In both the Palace of the Priors and in the Mercato Vecchio (the Old Market in the heart of the city), relations of trust built on face-to-face encounters were more important than abstract ideology. Piero was an intensely private man in a world that valued above all the lively give-and-take of the street corner.

The best contemporary portrait of Piero is the fine marble bust by Mino da Fiesole.* The sculpture reveals a handsome man with the cropped hair of an ancient Roman patrician and alert, thoughtful eyes. But there is something in the pugnacious thrust of his chin, a feature passed down to his oldest son, that suggests an inner strength his contemporaries little suspected.

A more engaging portrait emerges in Piero’s private letters that reveal a conscientious man deeply attached to his family and continually fretting over their uncertain future. He was a loving and devoted husband to Lucrezia Tornabuoni, a descendant of one of Florence’s most ancient families, and their correspondence reveals an unusually close bond. “[E]very day seems a year until I return for your and my consolation,” wrote Lucrezia from Rome to Piero, while Piero confessed that he awaited her arrival “with infinite longing.”

Piero was also a devoted, if sometimes overbearing, father, particularly with his oldest son, who could not leave town without being pursued by letters filled with unsolicited advice and constructive criticism. Piero’s letters alternately exhibit pride in his son’s precocious ability and an almost neurotic need to interfere in the smallest details of his conduct. “You will have received my letter of the 4th,” he wrote to Lorenzo in Milan, “telling you what conduct to pursue, all of which remember; in a word, it is necessary now for you to be a man and not a boy; be so in words, deeds and manners.” For the most part Lorenzo took his father’s nagging in good humor, though occasionally his exasperation shows through, as when he responded to yet another request for information, “I wrote to you two days ago, and for this reason I have little to say.”

The leaders of the current revolt were all prominent figures of the reggimento who viewed Cosimo’s death as an opportunity to satisfy their own ambition. Those like Agnolo Acciaiuoli, who had suffered exile with Cosimo when he ran afoul of the then ruling Albizzi family and shared in his triumphant return in 1434, felt that after thirty years of loyal service to the Medici cause their time had come. “Piero was dismayed when he saw the number and quality of the citizens who were against him,” wrote Machiavelli some sixty years after the events in his Florentine Histories, “and after consulting with his friends, he decided that he too would make a list of his friends. And having given the care of this enterprise to some of his most trusted men, he found such variety and instability in the minds of the citizens that many of those listed as against him were also listed in his favor.”

Machiavelli’s account captures something of the confusion of those days as once trusted friends were suspected of secret treachery. Considering the formidable array of figures now agitating for change, a betting man might have thought twice before wagering a few soldi on the Medici cause. They included such prominent and respected citizens as Luca Pitti, who, at least in his own mind, was Cosimo’s logical successor; the gifted orator Niccolò Soderini; Agnolo Acciaiuoli, a scholar and a friend of Cosimo’s whose thoughtful views carried great weight with his fellow citizens; and Dietisalvi Neroni, a shrewd political operator who had been a fixture within the highest circles of the reggimento.

In secret nighttime meetings in the city’s sacred buildings—the Party of the Plain favoring the monastery La Crocetta, while their adversaries favored the equally pious La Pietà—men began to look to their own defense, each suspecting the other of plotting the overthrow of the constitutional government. In a typically Florentine mixture of the sacred and profane, fervent prayers to the Virgin were often followed by calls to riot and mayhem.

By most measures the Medici were ill prepared for the coming contest. Piero’s poor health had thrust Lorenzo into a position of responsibility at an age when his companions were still completing their studies or were apprenticed in the family business. He had already served as his father’s envoy on crucial diplomatic missions, including the wedding of a king’s son and an audience with the newly elected pope. A few weeks earlier he had returned from a trip abroad to introduce himself to Ferrante, King of Naples, “with whom I spoke,” he wrote his father, “and who offered me many fine compliments, which I wait to tell you in person.” The importance for the Medici of such contacts with the great lords of Europe is suggested by Piero’s hunger for news of the meeting. Lorenzo’s tutor and traveling companion, Gentile Becchi, wrote an enthusiastic report of Lorenzo’s performance before the king. Referring to this account, Piero confessed, “Three times I read this for my happiness and pleasure.” Consorting with royalty provided this family of bankers much-needed prestige, though such social climbing if too vigorously pursued could also arouse the jealousy of their peers who believed that they were thus being left behind.*

The looming crisis would demand of Lorenzo a set of skills different from those he had recently practiced in the courts of great lords. The retiring Piero needed Lorenzo to act as the public face of the regime, the charismatic center of an otherwise colorless bureaucracy. As preparations were made for the coming battle, it was often to Lorenzo, rather than the ailing Piero, that men turned to pledge their loyalty. Marco Parenti, a cloth merchant of moderate means whose memoirs provide an eyewitness account of the events of these months, tells how the countryside was armed in the days leading up to the August crisis. “Thus it was arranged,” he wrote,

that there were 2000 Bolognese horsemen loyal to the duke of Milan. These were secretly ordered to be held in readiness for Piero; the Serristori, lords with a great following in the Val d’Arno, arranged with Lorenzo, son of Piero, a great fishing expedition on the Arno and many great feasts where were gathered peasants and their leaders, who, wishing to show themselves faithful servants of Piero, met amongst themselves and pledged themselves to Lorenzo. These pledges were accepted with much show as if it had not already been planned, though many were kept in the dark, to send them a few days hence in arms to Florence in support of Piero. And so it was arranged in other places, with other peasants and men who, when called on, would quickly appear in arms.

The fact that those bending their knees were often rude peasants and their lord a banker’s son gives to the proceedings a distinctly Florentine flavor, but it is clear that Lorenzo had already begun to take on some of the trappings of a feudal prince.

Lorenzo’s prominence, however, was actually a sign of weakness in the Medici camp. Florentines regarded youth as an unfortunate condition, believing that these giovanni—a term attached to all young men, including those in their twenties who had yet to assume the steadying yoke of marriage—were, like the entire female sex, essentially irrational and in thrall to their baser instincts. So far Lorenzo had given little indication that he was any better than his peers, having acquired a well-earned reputation for fast living. For the leaders of the Hill a trial of strength now, when the father was crippled and his heir not yet mature, was to their advantage. Jacopo Acciaiuoli, son of Agnolo, who had attended the meeting of King Ferrante and Lorenzo, reported to his father, “And returning to the arrival of Lorenzo, many fathers spend to get their sons known who would do better to spend so that they were not known.” Beneath the spiteful jab there is a more substantive message—that neither the ailing father nor his awkward son would put up much of a fight. The next few days would put this judgment to the test.

Indeed there was nothing in the biography of either Piero or Lorenzo to strike fear in an opponent. “[Piero] did not, to be sure, possess the wisdom and virtues of his father,” commented the historian Francesco Guicciardini (1483–1540), usually a fair judge of men, “but he was a good-natured and very clement man.” A kind heart, however, was not necessarily an advantage in the cutthroat world of Florentine politics; in the centuries of bloody strife that marred the history of the City of the Baptist, men of saintly disposition were notable by their absence.

Despite the rising tension, August 27 dawned in an atmosphere of deceptive calm. Elections for the new Signoria were scheduled for the following day, and Florentine citizens, the great majority of whom wished only to go about their daily lives undisturbed by the quarrels of their masters, were cautiously optimistic that the leaders of the opposing factions had pulled back from the precipice. Only the day before, Piero and his family had left Florence for their villa at Careggi, something he would never have contemplated had he believed a confrontation imminent. In a crisis anyone who found himself outside city walls could quickly be marginalized. It was just such a blunder that, thirty years earlier, almost cost Cosimo his life. Taking advantage of his temporary absence from the city, the government, led at the time by the Albizzi family, decided to move against their too-powerful rival. Upon returning to Florence, Cosimo had been arrested, threatened with execution, and ultimately sent into exile. The lesson could hardly have been lost on his son that leaving the city at a time of strife was a recipe for disaster.

Curiously, it was Dietisalvi Neroni, one of the leaders of the Hill, who had persuaded the Medici leader to take this vacation, promising that he, too, would retire to his villa, thus lessening the chances of a violent clash breaking out between their armed supporters. It was an apparently statesmanlike gesture that would allow the democratic process to go forward without interference.

Piero’s agreement suggests a misplaced confidence that the situation was moving in his direction, and there were in fact indications that the fortunes of the Medici party, which had reached a low ebb in the winter, were on the rebound. But the decisive factor may simply have been the poor state of his health; a few days earlier a flare-up of gout had confined him to his bed, making it almost impossible to conduct any serious business. Thus when Neroni held out an olive branch, Piero was only too happy grasp it.

Piero had failed to take the measure of Neroni, whose powers of dissimulation were apparently so highly developed that he was able to maintain cordial relations with the man whose destruction he plotted. Piero, not necessarily an astute judge of men at the best of times and now distracted by the pain in his joints, allowed himself to be taken in by Neroni’s conciliatory gestures. “[I]n order to better conceal his intent,” explains Machiavelli, “[Neroni] visited Piero often, reasoned with him about the unity of the city, and advised him.” Though Piero was aware that his onetime colleague had at least flirted with the opposition, Neroni was able to convince him that he was a man of goodwill who could act as a moderating influence on his fellow reformers.

Machiavelli portrays Neroni as an unprincipled schemer who set out to destroy his old friend in order to further his own career, but with him, as with all the leaders of the revolt of 1466, it is difficult to disentangle motives of self-interest from genuine idealism. Neroni does seem to have possessed some republican instincts, though it is uncertain if these were born of principle or sprang from a practical calculation that he could rise further as a champion of the people than as a Medici lackey. As Gonfaloniere di Giustizia (the Standard-Bearer of Justice, the head of state) in 1454 he was already an advocate of democratic reform, winning, according to one contemporary source “great goodwill among the people.” And in 1465 he had written to the duke of Milan that “the citizenry would like greater liberty and a broader government, as is customary in republican cities like ours.”

For the most part, however, Neroni prospered as a loyal servant of the Medici regime. It is unclear when ideological differences combined with frustrated ambition to turn him against his former allies, but as early as 1463 the ambassador from Milan reported to his boss that “Cosimo and his men have no greater or more ambitious enemy than Dietisalvi [Neroni].” In spite of these warnings, at the time of Cosimo’s death in 1464 Neroni was still one of Piero’s closest advisors.

Neroni’s first line of attack, recounts Machiavelli, was to engineer Piero’s financial collapse. He describes how Piero had turned to Neroni for advice following Cosimo’s death, but “[s]ince his own ambition was more compelling to him than his love for Piero or the old benefits received from Cosimo,” Neroni encouraged Piero to pursue policies “under which his ruin was hidden.” These policies included calling in many of the loans granted by Cosimo—often on easy terms and made for political rather than financial reasons—a move that caused a string of bankruptcies and added to the growing list of Piero’s enemies.

Despite his rival’s best efforts, however, Piero weathered the financial crisis, and by 1466 Neroni was growing impatient with half-measures. Guicciardini gives to Neroni the decisive role in the attempted coup: “[It was] caused in large part by the ambition of messer Dietisalvi di Nerone…. He was very astute, very rich, and highly esteemed; but not content with the great status and reputation he enjoyed, he got together with messer Agnolo Acciaiuoli, also a man of great authority, and planned to depose Piero di Cosimo.”

While Piero and his family headed to Careggi, Neroni and his confederates prepared to seize the government by force.

For generations, Careggi, with its fields and quiet country lanes, had served the Medici household as a refuge from the cares of the city. Cosimo had purchased for the philosopher Marsilio Ficino a modest farm close by at Montevecchio so that his friend would have the leisure to complete his life’s work, the translation of Plato from Greek to Latin. “Yesterday I went to my estate at Careggi,” Cosimo once wrote to Ficino, “but for the sake of cultivating my mind and not the estate. Come to us, Marsilio, as soon as possible. Bring with you Plato’s book on The Highest Good.…I want nothing more wholeheartedly than to know which way leads most surely to happiness.” Lorenzo, too, enjoyed the philosopher’s company, and later in life would convene at Careggi those informal gatherings of scholars and poets that historians dignified with the somewhat misleading label “the Platonic Academy,” finding the country air a suitable stimulus to deep thought.

Today, however, the villa at Careggi could provide no escape from the troubles of the city. The family had barely begun to settle in when the peace of the morning was shattered by the arrival of a horseman at the gates.* The messenger, his horse lathered from hours of hard riding, his clothes and skin blackened with dust, announced that he had come from Giovanni Bentivoglio, lord of Bologna, with an urgent message for the master of the house.

The messenger’s point of origin was sufficient to set off alarm bells. The ancient university town of Bologna was strategically placed near the passes through the Apennines to keep a watchful eye on anyone coming from the tumultuous Romagna; from here, an army descending on Tuscany from the north would easily be spotted. Bentivoglio was but one of many trusted allies of the Medici scattered throughout Italy and beyond who kept their eyes and ears open for any scrap of information that might be useful to their friends in Florence.

This morning’s letter brought news that Bentivoglio’s spies in the village of Fiumalbo had observed eight hundred cavalry and infantry under the banner of Borso d’Este, Duke of Modena and Marquis of Ferrara, setting out in the direction of Florence. To the startled Piero, their objective was clear—to join with the Medici’s enemies in the city and topple them from power.

Though Bentivoglio’s message has not survived, its contents are summarized by a letter written that same day by Nicodemo Tranchedini, the Milanese ambassador to Florence. In it he informs his master, Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan, that Piero had “received letters from the regime in Bologna, from D. Johane Bentivogli,” and that soldiers of the marquis of Ferrara were “already on the move to come here on the invitation of Piero’s enemies, with horse and riders of Bartholomeo Colione.”

For months the leaders of the Hill had been in close communication with Borso d’Este, a northern Italian lord whose schemes for self-aggrandizement were predicated on a change of government in Florence. In November 1465, the Milanese ambassador had reported to his employer that Borso’s agent, Messer Jacopo Trotti, “every day meets M. Luca, M. Angelo [Agnolo Acciaiuoli] and M. Dietisalvi [Neroni].” Given the fact that Piero was kept well informed of these machinations by Tranchedini, it is remarkable that he allowed himself to be lured from the city at this critical time.

If the motives of the Florentine rebels were a mixture of idealism and self-interest, those of Borso d’Este were unambiguous. Described by Pope Pius II in his memoirs as a “man of fine physique and more than average height with beautiful hair and a pleasing countenance,” Borso d’Este was also “eloquent and garrulous and listened to himself talking as if he pleased himself more than his hearers.” In his inflated self-regard he was little different from any number of petty princes who sold their military services to the highest bidder, nor did his taste for costly jewelry, his arrogance, and deceitfulness—other qualities noted by Pius—set him apart from his peers.

Technically a vassal of the pope, Borso was always looking for ways to expand his family’s territories at the expense of his neighbors. An important step in his campaign was the removal of the Medici, who were closely linked with his chief rival in the north, the powerful Sforza family of Milan. In June his representative in Florence had contacted Luca Pitti to suggest that “Piero be removed from the city.” It took almost two months of negotiation, but by late August the leaders of the Hill had decided to team up with the mercenary adventurer, inviting “the marquis of Ferrara [to] come with his troops toward the city and, when Piero was dead, to come armed in the piazza and make the Signoria establish a state in accordance with their will.”

Piero had grossly underestimated his enemies’ resolve, but he now moved swiftly to correct the situation. First he dashed off an urgent letter to Sforza, asking him to send his troops, some 1,500 of whom were stationed in Imola in Romagna, about fifty miles to the north, to intercept those of d’Este. Desperately seeking friends closer to home, Piero dictated a second letter to the leaders of the neighboring town of Arezzo, pleading that “upon receiving this you send me as many armed men as you can…and direct them here to me.”

Even more important was the task of mobilizing the pro-Medici forces within the city. Foreign armies could throw their considerable weight behind one faction or another, but victory and defeat would be determined largely inside the city walls. Here the rebels had a great advantage. Piero, in so much pain from gout that he could travel only by litter, would not arrive back in the city for hours, time the rebels could use to prepare the battlefield and set the terms of the engagement.

So it was that Lorenzo found himself this August morning hurrying back to Florence, accompanied only by a few companions as young and inexperienced as himself. It was Lorenzo’s mission to ride out ahead of the main party and to raise the Medici banner in Florence, ensuring as well that the gates remained in friendly hands long enough to permit Piero’s safe return. As the head of the household made his slow, painful way to Florence, the fate of the Medici regime would rest in the hands of a seventeen-year-old boy.

From the moment he left the fortified compound of Careggi, Lorenzo was on his guard. The countryside through which he passed was as familiar to him as the streets near the family palace in the city, the rolling hills and game-filled copses, destination of many a hunting expedition, a constant source of delight. Today, however, the landscape he loved felt menacing. Every low stone wall and ramshackle farmhouse provided a place of concealment, every patch of shade an opportunity for ambush.

Nothing disturbed the heavy air as the horsemen picked their way cautiously down the winding road. Tiny lizards darted through the underbrush, while hawks circled high overhead. Having completed most of the journey without incident, and with the walls of the city looming before him, Lorenzo brought his small group to a halt. Ahead lay a tiny hamlet known as Sant’Antonio (or Sant’Ambrogio) del Vescovo. Little more than a few buildings shimmering in the summer heat, there was nothing ominous in the rustic scene. But Lorenzo had reason to be wary. The village took its name from the archbishop (vescovo) of Florence, whose summer residence was attached to a small chapel there. The reigning archbishop of Florence was Giovanni Neroni, Dietisalvi’s brother. (His sacerdotal office could have provided little comfort: a bishop’s robes in Renaissance Italy were more often the costume of a political intriguer with a dagger in his belt than those of an unworldly man of God.) With Neroni’s recent treachery in mind, Lorenzo knew that to pass through the hamlet, his usual route from the villa to the city, he would have to place himself squarely in the lion’s den.

It was at this moment Lorenzo signaled to one of his party to remain some distance behind while he and the rest of his companions spurred their horses into motion and continued along the road to Florence. As the riders passed between the first of the buildings, armed men rushed out from behind walls and doorways, surrounding the riders, the points of their halberds glinting menacingly in the sun. Horses reared as Lorenzo and his companions unsheathed their swords. In the shadows men cocked crossbows. In the commotion apparently no one noticed the lone figure who turned his horse around and sped back along the road in the direction they had come.

The ambush at Sant’Antonio del Vescovo remains one of the more mysterious episodes in the annals of Florentine history. It is a puzzle that must be assembled from bits and pieces, the missing portions filled in with sound conjecture, since no contemporary report gives more than a brief, tantalizing mention. The most detailed account is that of Niccolò Valori, who included it in his biography of Lorenzo, written some thirty years later. But even this narrative raises as many questions as it answers:

[I]t was through the sound judgment of Lorenzo, though still young, that the life of Piero his father was saved; learning that awaiting him as he returned from Careggi were many conspirators who planned to kill him,[Lorenzo] sent word to those who were carrying [Piero] by litter (unable, sick as he was with gout, to travel any other way) not to continue by the usual route, but through a secret and secure way return to the city.[Lorenzo], meanwhile, riding along the usual path, let it be known that his father was right behind him; and having thus deceived the plotters, both were saved.

Francesco Guicciardini supplies some additional information, including the precise spot where the ambush took place. “[W]hen Piero went off to Careggi,” he wrote, “his enemies decided to murder him on his return. Armed men were placed in Sant’Ambrogio [sic] del Vescovo, which Piero usually passed on his way back to the city. They could avail themselves of that place because the archbishop of Florence was messer Dietisalvi’s brother.” Interestingly, Guicciardini ignores Lorenzo’s role in the drama, attributing their escape simply to “the good fortune of Piero and of the Medici.”*

Lorenzo himself never offered a full retelling of the day’s events, though it is possible that Valori’s version is based on Lorenzo’s recollections. References to the ambush must be teased from his own cryptic comments or from the equally oblique remarks of his friends. Lorenzo’s silence can be explained by his reluctance to talk about, or even admit the existence of, the many attempts made on his life. In 1477, when his life again appeared under threat from invisible assassins, he dismissed a warning from the Milanese ambassador: “and thanks to God, though I have been told by many: ‘watch yourself!,’ I have found none of these plots to be true, except one, at the time of Niccolò Soderini.” Thus the traumatic events of 1466 appear in Lorenzo’s correspondence only at the moment when an even more dangerous conspiracy was taking shape, and largely to make light of current threats. From this same period comes another suggestive letter, written by Lorenzo’s friend and tutor Gentile Becchi. Urging him to take the rumors of threats on his life seriously, he warns Lorenzo not to heed the counsel of “new Dietisalvis who will advise you to go to your villa like your father.”

Given Lorenzo’s own reticence, the ambush at Sant’Antonio del Vescovo must forever retain an element of mystery. Even Valori’s account contains many puzzling features. Why did those who confronted Lorenzo fail to take him into custody? Why did they accept Lorenzo’s assertion that his father was just around the corner, without at least holding him as a hostage? From Lorenzo’s few remarks it is clear that he felt his life had been in danger along the road from Careggi to Florence, but Valori’s narrative does not end in a violent clash. Instead, according to his friend’s retelling, Lorenzo manages to confound his enemies not through martial valor but through quick thinking and his powers of persuasion.

One might be tempted to dismiss the tale were it not for the fact that it conforms perfectly with what we know of Lorenzo’s character. The confrontation at Sant’Antonio may provide the first instance when Lorenzo was able to deflect the knives of his enemies using only his native wit, but it will not be the last. Time and again he showed a remarkable ability to talk his way out of tight situations. With his back to the wall, and his life hanging in the balance, Lorenzo was at his most convincing. A gift he was to display throughout his life—and one that would be crucial to his statecraft, allowing him to appeal to people from all walks of life—was to suit his language to the moment, effortlessly trading Latin epigrams with scholars or obscenities with laborers in a tavern. This earthier vocabulary would have served him well on this occasion, but his powers of persuasion would have done little good without the confusion and missteps that tend to unravel even the best-laid plans.

From the perspective provided by centuries in which scholars have been able to sift the evidence at leisure, the fact that Lorenzo was allowed to proceed unmolested seems an improbable bit of good fortune. But this view distorts the true situation. Lorenzo’s native wit no doubt played a part, but so did the natural perplexity of those who had been instructed to seize his father, the lord of Florence, and now had to make a snap decision with no instructions from their commanders. After a brief conversation, in which Lorenzo no doubt adopted a tone of light banter meant to put them at their ease, they let him go, having been convinced that soon enough the main prize would fall into their laps.

While they waited in vain for Piero to arrive, Lorenzo and the rest of his party made a dash for the city walls. As soon as he passed through the wide arch of the Porta Faenza, Lorenzo could breathe a little easier.* This was Medici country—the neighborhoods in the northwest corner of the city that in earlier centuries had mustered for war under the ancient banner of the Golden Lion. Familiar faces greeted him at every turn, local wine merchants, grocers, fishmongers, and stonemasons, with a fierce attachment to the few blocks where they were born and an equally fierce loyalty to the powerful family that lived among them. In his poem, “Il Simposio,” Lorenzo left a description of this neighborhood and its people that reflects an easy familiarity between the humble folks and the lord of the city:

I was approaching town along the road

that leads into the portal of Faenza,

when I observed such throngs proceeding through

the streets, that I won’t even dare to guess

how many men made up the retinue.

The names of many I could easily say:

I knew a number of them personally…

There’s one I saw among those myriads,

with whom I’d been close friends for many years,

as I had known him since we’d both been lads…

“Above all else stick together with your neighbors and kinsmen,” advised the Florentine patrician Gino Capponi, “assist your friends both within and without the city.” For decades Lorenzo’s forebears had acted upon this Florentine wisdom, knowing that men not masonry form the strongest bulwark in times of civic unrest. From the moment of his birth, seventeen years earlier, Lorenzo’s father had been preparing his son for just such a crisis, weaving around him an intricate web of mutual obligation, nurturing those relationships of benefactor and supplicant, patron and client, through which power was wielded in Florentine politics. In moments of upheaval, Lorenzo’s ability to draw on those relationships, to command the loyalty of his fellow citizens—above all of neighbors, friends, and kinsmen, bound together both by interest and by affection—would be vital to his family’s survival.

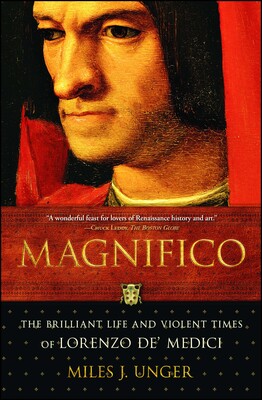

The Baptistery of San Giovanni, Florence (Miles Unger)

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (May 5, 2009)

- Length: 528 pages

- ISBN13: 9780743254359

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"This portrait of the 'uncrowned ruler of Florence' does great justice to this most intriguing of all Renaissance princes. Unger's diligent scholarship combines with an impelling narrative to give a full-bodied flavor of the splendors as well as the horrors of Lorenzo's remarkable reign." -- Ross King, author of Brunelleschi's Dome and Machiavelli

"A meticulous and entertaining study of one of the great characters of the Italian Renaissance, who ruled Florence during one of the most fascinating periods of Italy's turbulent history. Packed with incident and incisive research, this work succeeds in being both popular and scholarly." -- Paul Strathern, author of The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance

“Dazzling. . . . From the first sentence, Magnifico transports the reader to 15th-century Florence, a place of matchless splendor, both natural and man-made. Unger mines a rich lode of sources. . . . The result is an indelible personal profile and an enthralling account of both the glories and brutalities of the era.”

—David Takami, The Seattle Times

“Highly absorbing . . . provides a mesmerizing microscope for viewing the entire Italian Renaissance. . . . Magnifico is a wonderful feast for lovers of Renaissance history and art.”

—Chuck Leddy, The Boston Globe

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Magnifico Trade Paperback 9780743254359