Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Spoken from the Heart

Table of Contents

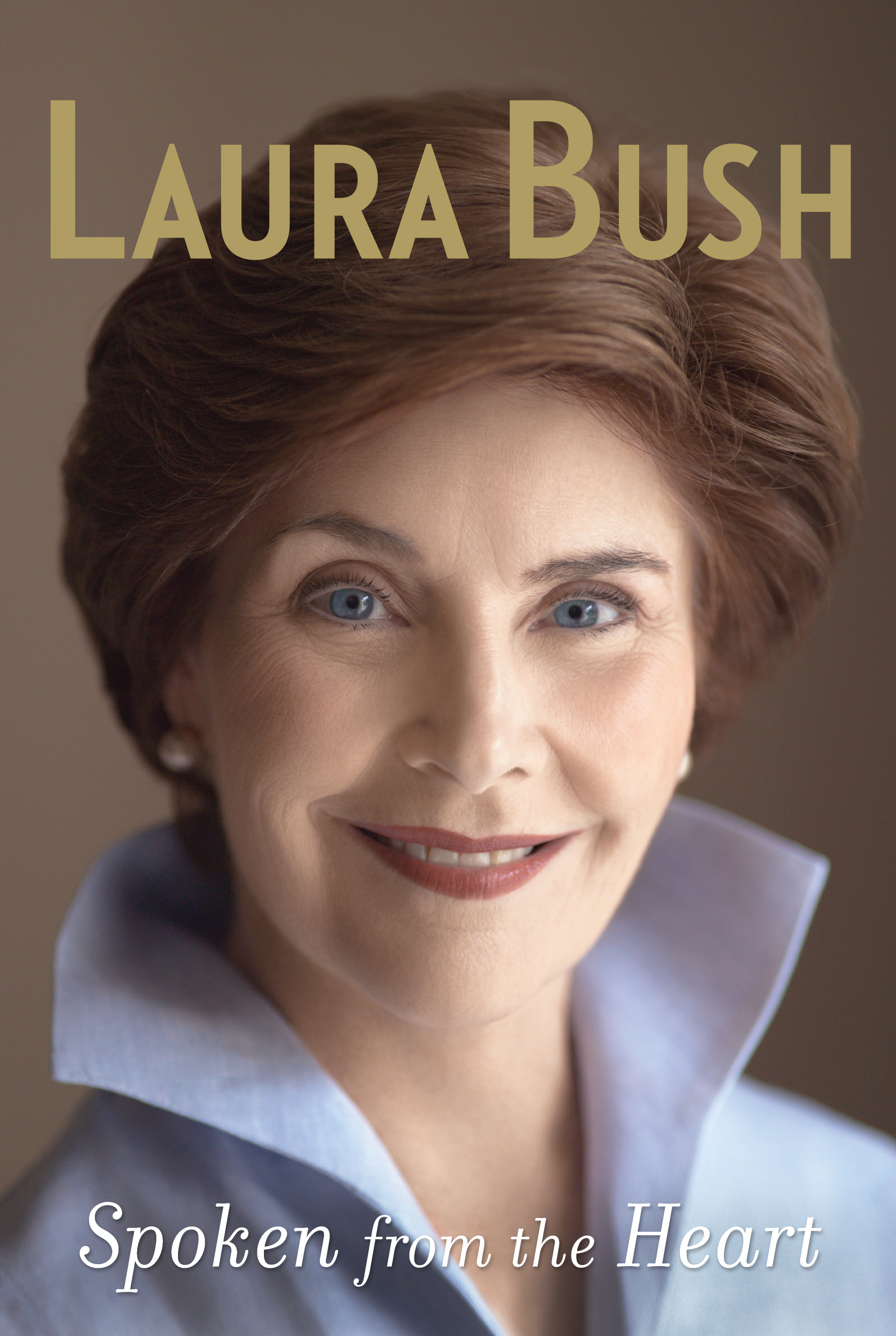

About The Book

Born in the boom-and-bust oil town of Midland, Texas, Laura Welch grew up as an only child in a family that lost three babies to miscarriage or infant death. She vividly evokes Midland's brash, rugged culture, her close relationship with her father, and the bonds of early friendships that sustain her to this day. For the first time, in heart-wrenching detail, she writes about the devastating high school car accident that left her friend Mike Douglas dead and about her decades of unspoken grief.

When Laura Welch first left West Texas in 1964, she never imagined that her journey would lead her to the world stage and the White House. After graduating from Southern Methodist University in 1968, in the thick of student rebellions across the country and at the dawn of the women's movement, she became an elementary school teacher, working in inner-city schools, then trained to be a librarian. At age thirty, she met George W. Bush, whom she had last passed in the hallway in seventh grade. Three months later, "the old maid of Midland married Midland's most eligible bachelor." With rare intimacy and candor, Laura Bush writes about her early married life as she was thrust into one of America's most prominent political families, as well as her deep longing for children and her husband's decision to give up drinking. By 1993, she found herself in the full glare of the political spotlight. But just as her husband won the Texas governorship in a stunning upset victory, her father, Harold Welch, was dying in Midland.

In 2001, after one of the closest elections in American history, Laura Bush moved into the White House. Here she captures presidential life in the harrowing days and weeks after 9/11, when fighter-jet cover echoed through the walls and security scares sent the family to an underground shelter. She writes openly about the White House during wartime, the withering and relentless media spotlight, and the transformation of her role as she began to understand the power of the first lady. One of the first U.S. officials to visit war-torn Afghanistan, she also reached out to disease-stricken African nations and tirelessly advocated for women in the Middle East and dissidents in Burma. She championed programs to get kids out of gangs and to stop urban violence. And she was a major force in rebuilding Gulf Coast schools and libraries post-Katrina. Movingly, she writes of her visits with U.S. troops and their loved ones, and of her empathy for and immense gratitude to military families.

With deft humor and a sharp eye, Laura Bush lifts the curtain on what really happens inside the White House, from presidential finances to the 175-year-old tradition of separate bedrooms for presidents and their wives to the antics of some White House guests and even a few members of Congress. She writes with honesty and eloquence about her family, her public triumphs, and her personal tribulations. Laura Bush's compassion, her sense of humor, her grace, and her uncommon willingness to bare her heart make this story revelatory, beautifully rendered, and unlike any other first lady's memoir ever written.

Excerpt

I finished dressing in silence, going over my statement again in my mind. I was very nervous about appearing before a Senate committee and having news cameras trained on me. Had the TV been turned on, I might have heard the first fleeting report of a plane hitting the North Tower of the World Trade Center at the tip of Manhattan as I walked out the door to the elevator. Instead, it was the head of my Secret Service detail, Ron Sprinkle, who leaned over and whispered the news in my ear as I entered the car a few minutes after 9:00 a.m. for the ride to the Russell Senate Office Building, adjacent to the Capitol. Andi Ball, now my chief of staff at the White House; Domestic Policy Advisor Margaret Spellings; and I speculated about what could have happened: a small plane, a Cessna perhaps, running into one of those massive towers on this perfect September morning. We wondered too if Hillary Clinton might decide not to attend the committee briefing, since the World Trade Center was in New York. We were driving up Pennsylvania Avenue when word came that the South Tower had been hit. The car fell silent; we sat in mute disbelief. One plane might be a strange accident; two planes were clearly an attack. I thought about George and wondered if the Secret Service had already hustled him to the motorcade and begun the race to Air Force One to return home. Two minutes later, at 9:16 a.m., we pulled up at the entrance to the Russell Building. In the time it had taken to drive the less than two miles between the White House and the Capitol, the world as I knew it had irrevocably changed.

Senator Kennedy was waiting to greet me, according to plan. We both knew when we met that the towers had been hit and, without a word being spoken, knew that there would be no briefing that morning. Together, we walked the short distance to his office. He began by presenting me with a limited-edition print; it was a vase of bright daffodils, a copy of a painting he had created for his wife, Victoria, and given to her on their wedding day. The print was inscribed to me and dated September 11, 2001.

An old television was turned on in a corner of the room, and I glanced over to see the plumes of smoke billowing from the Twin Towers. Senator Kennedy kept his eyes averted from the screen. Instead he led me on a tour of his office, pointing out various pictures, furniture, pieces of memorabilia, even a framed note that his brother Jack had sent to their mother when he was a child, in which he wrote, “Teddy is getting fat.” The senator, who would outlive all his brothers by more than forty years, laughed at the note as he showed it to me, still finding it amusing.

All the while, I kept glancing over at the glowing television screen. My skin was starting to crawl, I wanted to leave, to find out what was going on, to process what I was seeing, but I felt trapped in an endless cycle of pleasantries. It did not occur to me to say, “Senator Kennedy, what about the towers?” I simply followed his lead, and he may have feared that if we actually began to contemplate what had happened in New York, I might dissolve into tears.

Senator Judd Gregg of New Hampshire, the ranking Republican on the committee and one of our very good friends in the Senate—Judd had played Al Gore for George during mock debates at the ranch the previous fall—was also designated to escort me to the committee room, and he arrived just as I was completing the tour. Senator Kennedy invited us to sit on the couches, and he continued chatting about anything other than the horrific images unfolding on the tiny screen across the room. I looked around his shoulder but could see very little, and I was still trying to pay attention to him and the thread of his conversation. It seemed completely unreal, sitting in this elegant, sunlit office as an immense tragedy unfolded. We sat as human beings driven by smoke, flame, and searing heat jumped from the tops of the Twin Towers to end their lives and as firemen in full gear began the climb up the towers’ stairs.

I have often wondered if the small talk that morning was Ted Kennedy’s defense mechanism, if after so much tragedy—the combat death of his oldest brother in World War II, the assassinations of his brothers Jack and Robert, and the deaths of nephews, including John Jr., whose body he identified when it was pulled from the cold, dark waters off Martha’s Vineyard—if after all of those things, he simply could not look upon another grievous tragedy.

At about 9:45, after George had made a brief statement to the nation, which we watched, clustered around a small television that was perched on the receptionist’s desk, Ted Kennedy, Judd Gregg, and I walked out to tell reporters that my briefing had been postponed. I said, “You heard from the president this morning, and Senator Kennedy and Senator Gregg and I both join his statement in saying that our hearts and our prayers go out to the victims of this act of terrorism, and that our support goes to the rescue workers. And all of our prayers are with everyone there right now.” As I turned to exit, Laurence McQuillan of USA Today asked a question. “Mrs. Bush, you know, children are kind of struck by all this. Is there a message you could tell to the nation’s—” I didn’t even wait for him to finish but began, “Well, parents need to reassure their children everywhere in our country that they’re safe.”

As we walked out of the briefing room, the cell phone of my advance man, John Meyers, rang. A friend told him that CNN was reporting that an airplane had crashed into the Pentagon. Within minutes, the order would be given to evacuate the White House and the Capitol.

I walked back to Senator Kennedy’s office and then began moving quickly toward the stairs, to reach my car to return to the White House. Suddenly, the lead Secret Service agent turned to me and my staff and said that we needed to head to the basement immediately. We took off at a run; Judd Gregg suggested his private office, which was in the lower level and was an interior room. The Secret Service then told John that they were waiting for an Emergency Response Team to reach the Capitol. The team would take me, but my staff would be left behind. Overhearing the conversation, I turned back and said, “No, everyone is coming.” We entered Judd’s office, where I tried to call Barbara and Jenna, and Judd tried to call his daughter, who was in New York. Then we sat and talked quietly about our families and our worries for them, and the overwhelming shock we both felt.

Sometime after 10:00 a.m., when the entire Capitol was being emptied, when White House staffers had fled barefoot and sobbing through the heavy iron gates with Secret Service agents shouting at them to “Run, run!” my agents collected me. They now included an additional Secret Service detail and an Emergency Response Team, dressed in black tactical clothing like a SWAT force and moving with guns drawn. As we raced through the dim hallways of the Russell Building, past panicked staffers emptying from their offices, the ERT team shouted “GET BACK” and covered my every move with their guns. We reached the underground entrance; the doors on the motorcade slammed shut, and we sped off. The Secret Service had decided to take me temporarily to their headquarters, located in a nondescript federal office building a few blocks from the White House. Following the Oklahoma City bombing, their offices had been reinforced to survive a large-scale blast. Outside our convoy windows, the city streets were clogged with people evacuating their workplaces and trying to reach their own homes.

By the time I had reached my motorcade, Flight 93 had crashed in a Pennsylvania field and the west side of the Pentagon had begun to collapse. Judd Gregg walked alone to the underground Senate parking garage and retrieved his car, the last one left there. He pulled out of the garage and headed home, across the Fourteenth Street Bridge and past the Pentagon, thick with smoke and flame.

In the intervening years, Judd and I, and many others, were left to contemplate what if Flight 93 had not been forced down by its passengers into an empty field; what if, shortly after 10:00 a.m., it had reached the Capitol Dome?

We arrived at the Secret Service building via an underground entrance and were escorted first to the director’s office and then belowground to a windowless conference room with blank walls and a mustard yellow table. A large display screen with a constant TV feed took up most of one wall. Walking through the hallways, I saw a sign emblazoned with the emergency number 9-1-1. Had the terrorists thought about our iconic number when they picked this date and planned an emergency so overwhelming? For a while, I sat in a small area off the conference room, silently watching the images on television. I watched the replay as the South Tower of the World Trade Center roared with sound and then collapsed into a silent gray plume, offering my personal prayer to God to receive the victims with open arms. The North Tower had given way, live in front of my eyes, sending some 1,500 souls and 110 stories of gypsum and concrete buckling to the ground.

So much happened during those terrible hours at the tip of Manhattan. That morning, as the people who worked in the towers descended, water from the sprinkler system was racing down the darkened stairwells. With their feet soaked, for some the greatest fear was that when they reached the bottom, the rushing water would be too high and they would be drowned. A few walked to safety under a canopy of skylights covered with the bodies of those who had jumped. Over two hundred people jumped to escape the heat, smoke, and flames. I was told that Father Mychal Judge, the chaplain for the New York City Fire Department, who had come to offer aid, comfort, and last rites, was killed that morning by the body of someone who had, in desperation, hurled himself from the upper floors of one of those towers.

The early expectation was for horrific numbers of deaths. Manhattan emergency rooms and hospitals as far away as Dallas were placed on Code Red, expecting to receive airlifted survivors. Some fifty thousand people worked inside the towers; on a beautiful day, as many as eighty thousand tourists would visit an observation deck on the South Tower’s 107th floor, where the vistas stretched for fifty miles. Had those hijacked planes struck the towers thirty or forty or fifty minutes later, the final toll might well have been in the tens of thousands.

Inside Secret Service headquarters, I asked my staff to call their families, and I called the girls, who had been whisked away by Secret Service agents to secure locations. In Austin, Jenna had been awakened by an agent pounding on her dorm door. In her room at Yale, Barbara had heard another student sobbing uncontrollably a few doors down. Then I called my mother, because I wanted her to know that I was safe and I wanted so much to hear the sound of her voice. And I tried to reach George, but my calls could not get through; John Meyers, my advance man, promised to keep trying. I did know from the Secret Service that George had taken off from Florida, safe on board Air Force One. I knew my daughters and my mother were safe. But beyond that, everything was chaos. I was told that Barbara Olson, wife of Solicitor General Ted Olson, had been aboard the plane that hit the Pentagon. At one point, we also received word that Camp David had been attacked and hit. I began thinking of all the people who would have been there, like Bob Williams, the chaplain. Another report had a plane crashing into our ranch in Crawford. It got so that we were living in five-minute increments, wondering if a new plane would emerge from the sky and hit a target. All of us in that basement conference room and many more in the Secret Service building were relying on rumors and on whatever news came from the announcers on television. When there were reports of more errant planes or other targets, it was almost impossible not to believe them.

George had tried to call me from Air Force One. It is stunning now to think that our “state-of-the-art” communications would not allow him to complete a phone call to Secret Service headquarters, or me to reach him on Air Force One. On my second call from the secure line, our third attempt, I was finally able to contact the plane, a little before twelve noon. I was grateful just to hear his voice, to know that he was all right, and to tell him the girls were fine. From the way he spoke, I could hear how starkly his presidency had been transformed.

We remained in that drab conference room for hours, eventually turning off the repetitive horror of the images on the television. Inside, I felt a grief, a loss, a mourning like I had never known.

A few blocks away, in the Chrysler offices near Pennsylvania Avenue, a group of White House senior staff began to gather. After the evacuation, some of those who were new to Washington had been wandering, dazed and shaken, in nearby Lafayette Park. By midafternoon, seventy staff members had congregated inside this office building, attempting to resume work, while Secret Service agents stood in the lobby and forbade anyone without a White House pass from entering. Key presidential and national security staff and Vice President Cheney were still sealed away in the small underground emergency center deep below the White House.

As the skies and streets grew silent, there was a debate over what to do with George and what to do with me. The Secret Service detail told me to be prepared to leave Washington for several days at least. My assistant, Sarah Moss, was sent into the White House to gather some of my clothes. John Meyers accompanied her to retrieve Spot, Barney, and Kitty.

Then we got word that the president was returning to Washington. I would be staying as well. Late in the afternoon, I spoke to George again. At 6:30 we got in a Secret Service caravan to drive to the White House. I gazed out the window; the city had taken on the cast of an abandoned movie set: the sun was shining, but the streets were deserted. We could not see a person on the sidewalk or any vehicles driving on the street. There was no sound at all except for the roll of our wheels over the ground.

We drove at full throttle through the gate, and the agents hopped out. Heavily armed men in black swarmed over the grounds. Before I got out, one of my agents, Dave Saunders, who had been driving, turned around and said, “Mrs. Bush, I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry.” He said it with the greatest of concern and a hint of emotion in his voice. He knew what this day meant for us.

I was hustled inside and downstairs through a pair of big steel doors that closed behind me with a loud hiss, forming an airtight seal. I was now in one of the unfinished subterranean hallways underneath the White House, heading for the PEOC, the Presidential Emergency Operations Center, built for President Franklin Roosevelt during World War II. We walked along old tile floors with pipes hanging from the ceiling and all kinds of mechanical equipment. The PEOC is designed to be a command center during emergencies, with televisions, phones, and communications facilities.

I was ushered into the conference room adjacent to the PEOC’s nerve center. It’s a small room with a large table. National Security Advisor Condi Rice, Counselor to the President Karen Hughes, Deputy Chief of Staff Josh Bolten, and Dick and Lynne Cheney were already there, where they had been since the morning. Lynne, whose agents had brought her to the White House just after the first attack, came over and hugged me. Then she said quietly into my ear, “The plane that hit the Pentagon circled the White House first.”

I felt a shiver vibrate down my spine. Unlike the major monuments and even the leading government buildings in Washington, the White House sits low to the ground. It is a three-story building, tucked away in a downward slope toward the Potomac. When the White House was first built, visitors complained about the putrid scent rising from the river and the swampy grounds nearby. From the air, the White House is hard to see and hard to reach. A plane could circle it and find no plausible approach. And that is what Lynne Cheney told me had happened that morning, a little past 9:30, before Flight 77 crossed the river and thundered into the Pentagon.

At 7:10 that night, George strode into the PEOC. Early that afternoon, he had conducted a secure videoconference from Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska with the CIA and FBI directors, as well as the military Joint Chiefs of Staff and the vice president and his national security staff, giving instructions and getting briefings on the latest information. Over the objections of the Secret Service, he had insisted upon returning home. We hugged and talked with the Cheneys a bit. Then the Secret Service detail suggested that we spend the night there, belowground. They showed us the bed, a foldout that looked like it had been installed when FDR was president. George and I stared at it, and we both said no, George adding, “We’re not going to sleep down here. We’re going to go upstairs and you can get us if something happens.” He said, “I’ve got to get sleep, in our own bed.” George was preparing to speak to the nation from the Oval Office, to reassure everyone and to show that the president was safely back in Washington, ready to respond.

By 7:30 we were on our way up to the residence. I have no memory of having eaten dinner—George may have eaten on the plane. He tried to call the girls as soon as we were upstairs but couldn’t reach them. Barbara called back close to 8:00 p.m., and then George left to make remarks to the nation.

We did finally climb into our own bed that night, exhausted and emotionally drained. Outside the doors of the residence, the Secret Service detail stood in their usual posts. I fell asleep, but it was a light, fitful rest, and I could feel George staring into the darkness beside me. Then I heard a man screaming as he ran, “Mr. President, Mr. President, you’ve got to get up. The White House is under attack.”

We jumped up, and I grabbed a robe and stuck my feet into my slippers, but I didn’t stop to put in my contacts. George grabbed Barney; I grabbed Kitty. With Spot trailing behind, we started walking down to the PEOC. George had wanted to take the elevator, but the agents didn’t think it was safe, so we had to descend flight after flight of stairs, to the state floor, then the ground floor, and below, while I held George’s hand because I couldn’t see anything. My heart was pounding, and all I could do was count stairwell landings, trying to count off in my mind how many more floors we had to go. When we reached the PEOC, I saw the outline of a military sergeant unfolding the ancient hideaway bed and putting on some sheets.

At that moment, another agent ran up to us and said, “Mr. President, it’s one of our own.” The plane was ours.

For months afterward at night, in bed, we’d hear the military jets thundering overhead, traveling so fast that the ground below quivered and shook. They would make one pass and then, three or five minutes later, make another low-flying loop. I would fall asleep to the roar of the fighters in the skies, hearing in my mind those words, “one of our own.” There was a quiet security in that, in knowing that we slept beneath the watchful cover of our own.

Waking the next morning, I had the sensation of knowing before my eyes opened that something terrible had happened, something beyond comprehension, and I wondered for a brief instant if it had all been a dream. Then I saw George, and I knew, knew that yesterday would be with us, each day, for all of our days to come.

© 2010 Laura Bush

Reading Group Guide

Get a FREE ebook by joining our mailing list today! Plus, receive recommendations for your next Book Club read.

INTRODUCTION

From the flat, dusty streets of Midland, Texas, in the heart of the boom-and-bust American oil patch, to the gleaming columns and glistening marble hallways of the White House, Laura Welch Bush traveled a rare path. But many readers will find much to share in her particular story—from private family grief and a tragic twist of fate to waiting years for love and her struggle for much-wanted children. Use our reader’s guide to help re-examine Laura Bush’s private years and her life in the public eye.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

THE FORMATIVE YEARS IN MIDLAND, TEXAS YEARS

- Laura Bush’s Spoken from the Heart begins with a story of loss: the death of her premature, newborn baby brother when Laura was just two-and-a-half years old. The theme of loss is woven throughout the book, the loss of two other baby siblings; the loss of her friend, Mike Douglas, in the car crash; the loss of her father to dementia; even the loss of privacy and anonymity first when she marries into the Bush family and then when her husband enters politics. How do you think these losses shaped her life and shaped her outlook? Did they make her more resilient or more guarded? Did reading about this legacy of loss change your own impressions and opinions of her?

- West Texas and Laura Bush’s Texas roots are a major component of her story. On page 20, she writes, “There was an underlying sense of hardship, a sense that the land could quickly turn unforgiving.” And on p. 121, “People in West Texas believe that they think differently, and to a large degree they do….Those who live there are direct and blunt to the point of hurt sometimes. There is not time for artifice; it looks and sounds ridiculous amid the barren landscape.” How did the land of West Texas shape Laura and the Welch family? Did you come away from the book thinking that people from that part of the United States are indeed different? What were the most noticeable differences or characteristics for you?

- Laura Bush was also deeply shaped by being an only child. On page 6, she says, “I remember as a small girl looking up at the darkening night sky, waiting for the stars to pop out one by one. I would watch for that first star, for its faint glow, because then I could make my wish. And my wish on a star any time that I wished on a star was that I would have brothers and sisters.” Do you think her response might have been different if her parents hadn’t wanted other babies so much? Do you think that there is an inherent loneliness born out of being an only child or did Laura’s circumstances make her feel it more acutely? What was your response to her mother’s decision to send young Laura on “solo picnics”?

- One aspect of Laura Bush’s West Texas life that comes through strongly in the book is the code of silence. Her family and others did not talk about veterans’ World War II experiences; her mother and father did not speak of the lost babies; and no one spoke of the horrible car crash the day after she turned 17. Her mother didn’t want to speak about her father’s drinking. Do you think this silence is unique to the culture of the area or to the era of the 1940s, 50s, and early 60s? What is your reaction to this code of silence, compared to our own time, when tell-alls and personal confessions are far more the norm and the rule?

- Laura Bush recounts in devastating detail the car accident that claimed the life of her high school friend. What were your own emotions reading her story of that night and the days that followed? Do you think it would have helped if she had gone to the funeral? What would you now say to someone in that position as a result of what Laura has described and discussed? Should her family and friends have talked about the crash and its aftermath? How do you imagine the silence about the accident shaped her? Do you think she has forgiven herself?

FINDING HER WAY AS AN ADULT

- Laura Bush entered college less than a year after John F. Kennedy was assassinated and graduated a few weeks after the deaths of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King. Women’s liberation was also on the cultural agenda. How is her own life during that period reflective or not reflective of the 1960s in the United States? How did that turbulent period affect her decisions, choices, and beliefs?

- From the time that she was a little girl, friendship was deeply important to Laura Bush. Yet she also made some very different choices from many of her friends: she did not marry early; she chose a traditional job, but wanted to work in more challenging environments; and she was restless, moving from town to town. What was your response to that era of her life? What do you think she was looking for? Why do you think the 20s can be such a restless period in a person’s, particularly a woman’s, life?

- When Laura Bush tells the story of her first, semi-blind date with George Bush, she ends by saying that perhaps if they had met at some other point, things would not have worked out, but on that night, “it was the right timing for both of us.” What, to you, was the most surprising part of their courtship and decision to marry? Do you think it is possible to meet someone and just know that he or she is right for you? What aspects of their lives do you think were the most important anchors for their marriage?

- Laura Bush begins her marriage with a political campaign. What do you think are the pros and cons of marrying into a political family? What do you imagine were the biggest difficulties for her coming from a small, private family and joining a large, sprawling, high-profile political family? What were your reactions to how she negotiated her new role?

- When George and Laura Bush got married, she returned to live in Midland, Texas—and stayed far out of the Washington political spotlight for most of George HW Bush’s presidency. How do you think those years of living as adults in their childhood hometown shaped both of the Bushes?

- Laura and George Bush struggled to have children, eventually filing for adoption and trying fertility treatments. She notes, “The English language lacks the words to mourn an absence….for someone who was never there at all, we are wordless to capture that particular emptiness.” How hard is it still to talk about infertility? Are we as a culture sensitive enough to couples who are struggling to have a child? What part of Laura Bush’s story of her efforts to have children resonated most with you?

- Much of Midland, Texas’s social culture revolved around drinking. Why do you think so much heavy drinking was acceptable for so many decades? Was there anything about Midland that made it a drinking town, or was it not that different from other parts of the United States in those years? What did you think of the fact that both Laura and her mother married men who drank almost every day? How would you compare the ways in which each woman handled the situation?

- Laura Bush and her mother-in-law, Barbara Bush, are both strong women, but in very different ways. What aspects of their relationship surprised you the most? What are some of the greatest tensions, generally, between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law? Who do you think was most responsible for the tone of Laura and Barbara’s relationship, in the beginning and, later, over time? Who should take the lead in an in-law relationship?

- Just as her husband is entering political life to run for governor of Texas, Laura Bush’s beloved father is succumbing to the worst of dementia. After he dies, she has a number of regrets about things she wishes they had done, from playing more music to making sure that he was at George’s gubernatorial swearing in—many of which she discusses on pp. 137-38. What side of Laura Bush do we see in this episode? What, to you, are the most important issues that she explores about care giving and the loss of a parent?

STEPPING ON TO THE NATIONAL STAGE: THE WHITE HOUSE YEARS

- Do you think that Laura Bush changes when her husband enters national politics? If so, how does she change? Does her story or the way that she tells it change? What do you think is the cause of those changes?

- On pp. 184-186, Laura Bush discusses some of the behind-the-scenes components of living at the White House—including the costs, having her hair styled each day, the clothing she needed to buy for herself, even the costs of meals. What were some of the things that you found most intriguing about her descriptions of life inside the White House? Why do you think some First Families find the White House lonely? What did you learn about the scrutiny political families face and the lack of privacy? Is it a fair trade-off?

- 9-11 was a transformative moment for the nation and also for the Bush family. What did you think of Laura Bush’s experience that morning in Senator Ted Kennedy’s office, as described on pp. 198-199? How might you have reacted to being escorted out of the Capitol by men with automatic weapons and being rushed to a basement holding room where you could not reach your husband? Knowing her life story up to now, what do you think made Laura Bush become “the comforter-in-chief”?

- Did your views of the war on terror change in any way after you read the book? What do you think now of the decision to send troops to Afghanistan and later to Iraq? How do you think Laura Bush saw her role as the wife of a wartime president?

- Do you agree that we, both in the United States and the West, have an obligation to help the women of Afghanistan? What was the most difficult part of the situation in Afghanistan for you to understand?

- As First Lady, Laura Bush took on many difficult causes, from women in Afghanistan, to a breast cancer initiative in the Arab world (a place where the subject is all but taboo), to malaria and AIDS in Africa, to a major initiative, Helping America’s Youth, focused on at-risk boys and also girls. Why do you think she chose these types of challenging causes? What sort of difference can a first lady make in addressing these types of problems? Did you know that she had such a busy and demanding agenda? If not, why do you think she didn’t get as much attention for her causes and her role?

- Laura Bush does take on the media, writing on p. 353, “Some of it was sloppiness, reporters who didn’t know an issue and got basic facts wrongs. But some of it was bias, where journalists, rather than being objective, could not put their own emotions and assumptions aside.” Do you think that is a fair criticism? Do you think Laura Bush was treated fairly by the media? How serious do you think the problem of media bias is and how much does it affect what we know and how we perceive issues and also our political leaders?

- George W. Bush was subjected to very harsh political criticism. The Majority Leader of the U.S. Senate called him a “loser” and a “liar.” Laura Bush writes, “The president doesn’t have the luxury of having like a smart-aleck kid on a school playground; he has to work not just with Congress, but with leaders around the world.” Do you agree that the criticisms were over the line and excessively personal? Do you think that people in the public arena should choose their words with more care? What are our responsibilities to maintain a free and healthy debate in the country, so that there can also be a free and passionate exchange of views?

- First Ladies are expected to have policy initiatives, but also to be flawless entertainers, receiving scrutiny for state dinners and a host of other events, even holiday themes and decorations. After reading Spoken from the Heart, do you think that we need to update our view of the role of First Lady or is the mix of responsibilities about right?

- What most surprised you about the book and about Laura Bush? What kind of person did you think she was before you read the book, and what kind of person do you see her as now?

- What do you think is Laura Bush’s legacy? What are the lessons you will take away from her public and from her private life?

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (May 4, 2010)

- Length: 464 pages

- ISBN13: 9781439155202

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Mrs. Bush’s delicate rendering . . . sets this book far apart from the typical score-settling reminiscences of politicians or their spouses. . . . Spoken from the Heart reveals Laura Bush to be a beautiful writer, a keen observer and a tender soul who drew on her roots to live a life in the public eye with compassion and grace.”—Wall Street Journal

“This is Laura Bush, unplugged. . . . She comes across with a keener eye, a sharper tongue and a readier laugh than in interviews during the eight years while her husband was president.”—USA Today

“A deeply felt, keenly observed account of her childhood and youth in Texas—an account that captures a time and place with exacting emotional precision and that demonstrates how Mrs. Bush’s lifelong love of books has imprinted her imagination.”—New York Times

“Laura Bush writes as vividly of her upbringing in the bleak and unforgiving oil-patch towns of West Texas as Buzz Bissinger did in his classic Friday Night Lights.”—Bloomberg

“Wide-ranging . . . candid . . . deeply personal. . . . A beautifully written book.”—Ann Curry, NBC’s “Today” Show

“A real, moving, intimate story.”—People

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Spoken from the Heart Hardcover 9781439155202(3.4 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Laura Bush Photograph copyright Brigitte Lacombe 2010(7.3 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit