Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

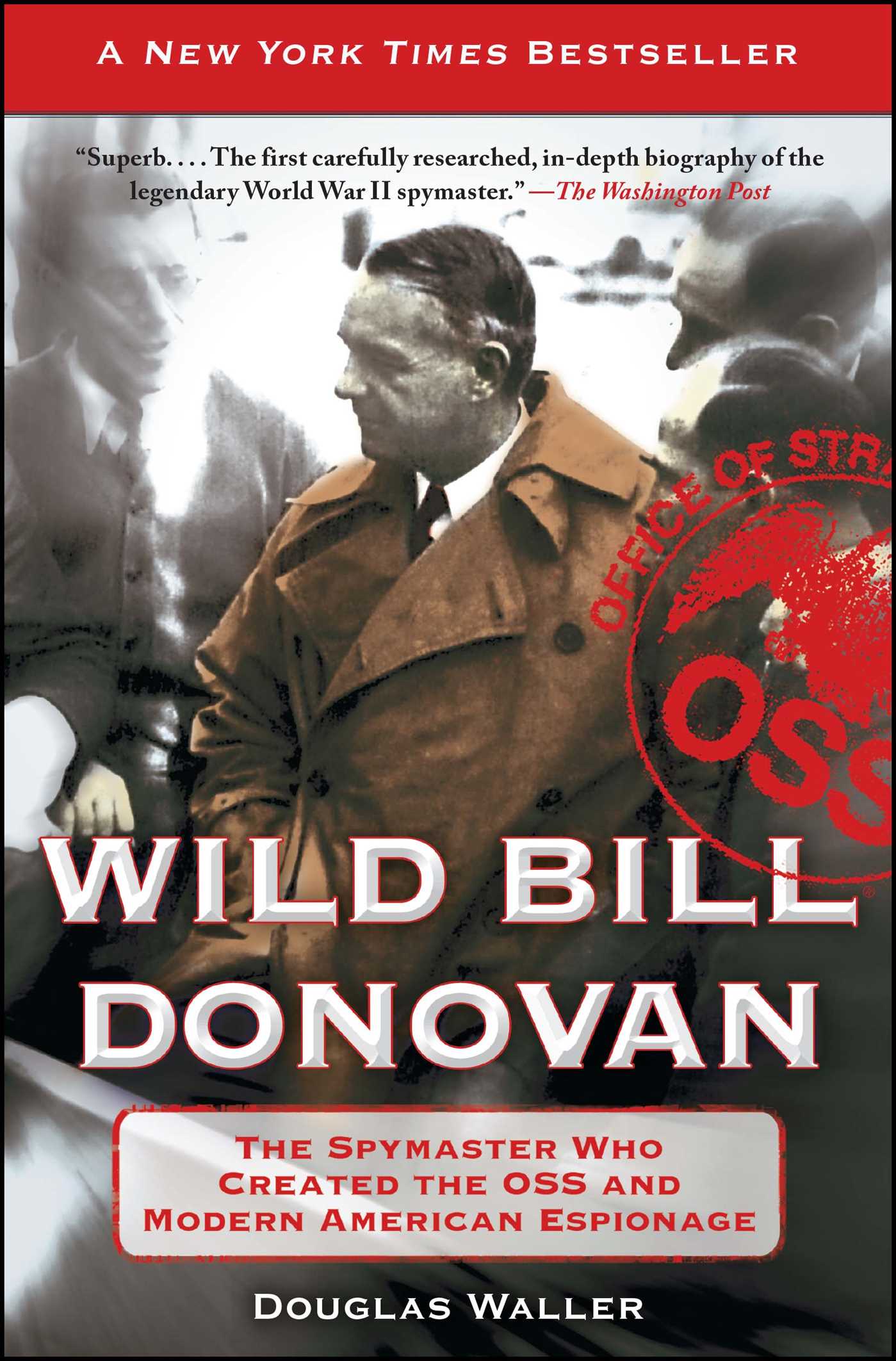

About The Book

“Entertaining history…Donovan was a combination of bold innovator and imprudent rule bender, which made him not only a remarkable wartime leader but also an extraordinary figure in American history” (The New York Times Book Review).

He was one of America’s most exciting and secretive generals—the man Franklin Roosevelt made his top spy in World War II. A mythic figure whose legacy is still intensely debated, “Wild Bill” Donovan was director of the Office of Strategic Services (the country’s first national intelligence agency) and the father of today’s CIA. Donovan introduced the nation to the dark arts of covert warfare on a scale it had never seen before. Now, veteran journalist Douglas Waller has mined government and private archives throughout the United States and England, drawn on thousands of pages of recently declassified documents, and interviewed scores of Donovan’s relatives, friends, and associates to produce a riveting biography of one of the most powerful men in modern espionage.

Wild Bill Donovan reads like an action-packed spy thriller, with stories of daring young men and women in the OSS sneaking behind enemy lines for sabotage, breaking into Washington embassies to steal secrets, plotting to topple Adolf Hitler, and suffering brutal torture or death when they were captured by the Gestapo. It is also a tale of political intrigue, of infighting at the highest levels of government, of powerful men pitted against one another.

Separating fact from fiction, Waller investigates the successes and the occasional spectacular failures of Donovan’s intelligence career. It makes for a gripping and revealing portrait of this most controversial spymaster.

He was one of America’s most exciting and secretive generals—the man Franklin Roosevelt made his top spy in World War II. A mythic figure whose legacy is still intensely debated, “Wild Bill” Donovan was director of the Office of Strategic Services (the country’s first national intelligence agency) and the father of today’s CIA. Donovan introduced the nation to the dark arts of covert warfare on a scale it had never seen before. Now, veteran journalist Douglas Waller has mined government and private archives throughout the United States and England, drawn on thousands of pages of recently declassified documents, and interviewed scores of Donovan’s relatives, friends, and associates to produce a riveting biography of one of the most powerful men in modern espionage.

Wild Bill Donovan reads like an action-packed spy thriller, with stories of daring young men and women in the OSS sneaking behind enemy lines for sabotage, breaking into Washington embassies to steal secrets, plotting to topple Adolf Hitler, and suffering brutal torture or death when they were captured by the Gestapo. It is also a tale of political intrigue, of infighting at the highest levels of government, of powerful men pitted against one another.

Separating fact from fiction, Waller investigates the successes and the occasional spectacular failures of Donovan’s intelligence career. It makes for a gripping and revealing portrait of this most controversial spymaster.

Excerpt

Wild Bill Donovan Chapter 1

First Ward

SKIBBEREEN, a coastal town on the southern tip of Ireland in County Cork, had a reputation for producing cultured people, or so went the lore among county folk. Timothy O’Donovan, who had been born in 1828, fit that stereotype. Raised by his uncle, a parish priest, Timothy had become a church schoolmaster. It was too humble an occupation, however, for the Mahoney family, who owned a large tract of land in the northern part of Cork and who took a dim view of their daughter, Mary, spending so much time with a lowly teacher eight years her senior. But the Mahoneys could not stop Timothy and Mary from falling in love. Attending the wedding of another couple they decided they would do the same—immediately. They eloped that day.

Growing poverty in Ireland and the promise of opportunity in America were powerful lures for the O’Donovan newlyweds, as they were for millions of young Irish men and women. They landed in Canada in the late 1840s with money Mary’s father grudgingly had given them to resettle and made their way across the southern border to Buffalo in western New York.

A boomtown, Buffalo was fast becoming a major transshipment point in the country for Midwest grain, lumber, livestock, and other raw materials dropped off at its Lake Erie port, then moved east on the Erie Canal to Albany and on to the Eastern Seaboard. The O’Donovans, who soon dropped the “O” from their name, settled in southwest Buffalo’s First Ward, a rough, noisy, polluted, and clannish neighborhood cut off from the rest of the city by the Buffalo River, where several thousand Irish families packed into clapboard shanties along narrow unpaved streets. Timothy could walk to the grain mills along the river, where he found employment as a scooper shoveling grain out of the holds of ships for the mills. Scooping was considered a good job, which made Timothy enough money to feed Mary and the ten children she eventually bore. He became a teetotaling layman in one of First Ward’s Catholic churches and allowed his home to be used by local Fenians, a secret society dedicated to independence for the Irish Republic.

The Donovans’ fourth child, Timothy Jr., who was born in 1858, proved to be a rebellious son who often played hooky from school and defied his father’s pleas that he attend college and make something of himself. Instead, “Young Tim,” as he had been called at home, went to work for the railroad, becoming a respected superintendent at the yard near Michigan Avenue. At one point the Catholic bishop of Buffalo called on him to calm labor unrest at the docks, which Young Tim succeeded in doing. He continued to display an independent streak, becoming an active Republican in his ward, a rarity for Irish Americans of his day, who voted practically lockstep with the Democratic Party.

In 1882, Young Tim married Anna Letitia Lennon, a brown-haired Irish beauty the same age as he (twenty-four), who had been orphaned when she was ten. Her father, a watchman for a grain elevator, had fallen off a wharf and drowned in the Buffalo River. Her mother had died the year before from an epidemic sweeping through First Ward. Anna had gone to live with cousins in Kansas City, but returned to Buffalo by the time she was eighteen, now a mature young woman with a love for fine literature.

To save money, the newlyweds went to live with the older Donovans at their 74 Michigan Avenue home; “Big Tim” (as the father was called) lived on the first floor with his family. Young Tim’s family took the second floor and the house’s enormous attic that had been converted into a dormitory. By then, Young Tim had come to regret profoundly that he had not studied in school and gone to college. He began to read widely, stocking hundreds of books in the library of the nicer two-story brick home he and Anna later bought outside of First Ward on Prospect Avenue. Tim also eventually left the rail yard to take a better job as secretary for the Holy Cross Cemetery. He and Anna became “lace curtain Irish,” the term the jealous “shanty Irish” of First Ward used for families that moved up and out. By the time he was middle-aged, Tim and his family were even listed in the Buffalo Blue Book for the city’s prominent—no small feat considering that as a young man looking for work he saw signs hanging from many businesses that read “No Irish Need Apply.”

It was while they were living with his father that Tim and Anna had their first child, whom they named William Donovan. He was born on New Year’s Day, 1883, at the Michigan Avenue home, delivered by a doctor who made a house call. Mary chose “William,” which was not a family name. The young boy picked his own middle name, “Joseph,” later at his confirmation. His parents called him “Will.”

Anna had another boy, Timothy, the next year and Mary was born in 1886. Disease killed the next four children shortly after birth or in the case of one, James, when he was four months shy of his fourth birthday. Vincent arrived by the time Will was eight and Loretta (her siblings called her “Loret”) came when the family had moved to Prospect Avenue and Will was fifteen.

From Anna’s side of the family came style and etiquette and the dreams of poets. From Tim came toughness and duty and honor to country and clan. At night the parents would read to Will and the other children from their books—Will’s favorites were the rich, nationalistic verses of Irish poet James Mangan. Saturday nights, when the workweek was done, Tim would often take the three boys with him to the corner saloon (practically every corner of First Ward had a saloon) to listen to the men argue about the Old Country and sing Irish ballads. Fights often broke out; a young man who walked into a First Ward pub always looked for the exit in case he had to get out fast. Tim, who like his father abstained from alcohol and also tobacco, sipped a ginger ale while Will and his brothers snitched sandwiches piled high on the bar.

Will adored his mother and tried to control his violent temper for her sake. But there was an intensity to the oldest Donovan son; he rarely smiled and fought often with other boys in the neighborhood (who could never make him cry) or with his brothers, who tended to be milder mannered. Tim, who could be hotheaded at times himself, finally bought boxing gloves and set up a ring in the backyard to let the three boys punch until they wore themselves out.

Both parents were stern disciplinarians and insisted that their children have proper schooling. When he was old enough to start, Will awoke early each morning and spent an hour taking the streetcar and walking to Saint Mary’s Academy and Industrial Female School on Cleveland Avenue north of First Ward. The school, which became known as “Miss Nardin’s Academy” after its founder, Ernestine Nardin, offered classes for working women in the evening; during the day, boys and girls attended for free. Will, who attended the academy until he was twelve, proved to be an erratic student. His spelling grades were poor. He earned barely a C in geography. But the nuns who taught him found him unusually well read for a child his age with an almost insatiable appetite for books. He also was not shy about standing in front of the class and reading stories or orations.

At thirteen, Will enrolled at Saint Joseph’s Collegiate Institute, a Catholic high school downtown run by the Christian Brothers. Saint Joseph’s charged tuition but James Quigley, the six-foot-tall bishop of Buffalo, who knew the Donovan family well, paid Will’s fee from a diocese fund. The school stressed public speaking, debating, and athletic competition. Will Donovan thrived. He acted in school plays, won the Quigley Gold Medal one year for his oration titled “Independence Forever,” and improved his grades. He also played football for Saint Joseph’s and was scrappy and ferocious on the field.

In Irish Catholic families, it was assumed that one of the boys would enter the priesthood. Tim and Anna never even hinted at the notion with their sons, but Will expected he would be the one when he graduated from Saint Joseph’s in 1899. To make up his mind he enrolled in Niagara University, a Catholic college and seminary on the New York bank of the Niagara River separating the United States from Canada. The school was founded to “prepare young men for the fight against secularism and . . . indifference to religion,” as one university history put it.

Donovan, however, soon disabused himself of a religious calling as he plunged into his studies at Niagara. Father William Egan, a professor at the university who became another of Donovan’s religious mentors, gently advised him that he did not seem cut out for the cloth. Donovan also concluded “he wasn’t good enough to be a priest,” Vincent recalled. But for someone who had decided to take the secular road, Donovan still had a lot of fire and brimstone left in him. He won one oratorical contest with a speech titled “Religion—The Need of the Hour.” In florid prose he condemned anti-Christian forces corrupting the nation—a theme pleasing to the ears of the Vincentian fathers judging him. “We stand in the presence of these evils which threaten to overwhelm the world and hurl it into the abyss of moral degradation,” Donovan railed.

After three years of what amounted to prep school at Niagara, Father Egan convinced Donovan that the legal profession might be his calling (he certainly had the windpipes for the courtroom) and wrote him a glowing recommendation for Columbia College in New York City—which helped get him admitted in 1903 despite mediocre grades.

He continued to be an average student at Columbia, but the college gave him the opportunity to widen his intellectual horizon and explore ideas beyond Catholic dogma (though like Donovan, a large majority of his classmates professed to be conservative Republicans). At one point Donovan even questioned whether he wanted to remain in the Catholic Church and started attending services for other denominations and religions, including the Jewish faith, to check them out. He finally decided to stick with Catholicism.

Donovan soaked up campus life. He won the Silver Medal in a college oratory contest, rowed on the varsity crew squad, ran cross-country, and was the substitute quarterback for the college football team. Football elevated him to near campus-hero status by his senior year, when the coach let him in the game more often. (His gridiron career ended abruptly during the sixth game of the 1905 season when a Princeton lineman hobbled him with a tackle.) In the senior yearbook his classmates voted him the “most modest” and one of the “handsomest.”

Donovan was handsome, his dark brown hair brushed neatly to the side, his face angular but with soft features that showed manliness yet gentleness, and those captivating blue eyes. Young women found him irresistible and at Columbia Donovan began going out with them, gravitating toward girls with highbrow pedigrees. He dated Mary Harriman, a free spirit who attended nearby Barnard College and whose father was railroad tycoon Edward Henry Harriman. His most serious romance developed with Blanche Lopez, the stunningly beautiful daughter of Spanish aristocrats resettled in New York City, whom Donovan had met at a Catholic church near Columbia.

Donovan graduated with Columbia’s Class of 1905, earning a bachelor of arts degree. He immediately enrolled in Columbia Law School, which took him two years to complete. Donovan became a serious student. He caught the eye of Harlan Stone, a highly respected New York lawyer and academic who taught him equity law. Stone, who never looked at notes or raised his voice at students during class, was impressed by the kid from a rough Irish neighborhood, who asked and answered questions in such a thoughtful, measured tone. Stone was Donovan’s favorite professor—and over the years, a close friend.

One of Donovan’s classmates was Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The two never mingled, however, because they had absolutely nothing in common. Roosevelt came from a wealthy New York family, he had attended the country’s best schools (Groton, then Harvard), he was never particularly good at sports, he was not too serious a law student, and he was already married. Roosevelt saw Donovan on campus frequently but paid him no attention. Donovan, for his part, had no interest in the dandy from Hyde Park.

DONOVAN RETURNED to bustling Buffalo, worried that he had rushed through college and law school, that he wasn’t truly educated, not fully prepared for the courtroom. He moved back in with Tim and Anna at the Prospect Avenue house and seemed to them aimless at first. They were uncertain how their son, with all his fancy schooling, would now turn out. He mulled entering politics, an idea that horrified friends and relatives as a perfectly good waste of a fine education. After more than a year of indecision, Bill Donovan (only his parents and siblings still called him Will) finally joined the venerable law firm of Love & Keating on fashionable Ellicott Square in 1909, earning almost $1,800 a year as an associate—a respectable enough salary that guaranteed him the “promise of future success,” as one local newspaper noted. Two years later, Donovan struck out on his own, forming a law partnership with Bradley Goodyear, a Columbia classmate from a prominent Buffalo family. Setting up an office in the Marine Trust Building downtown, they specialized in civil cases, which ranged from defending automobile drivers and their insurance companies in lawsuits (their bread-and-butter work) to settling a dispute (in one case) among neighbors over the death of a dog. Donovan and Goodyear took on associates. Three years later they merged with a firm run by one of Buffalo’s most well-connected lawyers—John Lord O’Brian, who had advised President William Howard Taft and would have the ear of future presidents on intelligence and defense issues.

Goodyear and O’Brien opened doors for Donovan in Buffalo society and among the exclusive clubs and civic organizations, where more important business contacts were made and lucrative deals were hatched. Donovan was admitted to the Saturn Club on Delaware Avenue and to the Greater Buffalo Club, where the city’s millionaires hung out. He joined the sailing club, organized a tennis and squash club with Goodyear (a magnet for business contacts), bought property with his spare cash, ordered his suits from a tailor in New York City, and began donating to the local Republican committee (required for a businessman on his way up).

As he moved up in Buffalo society, Donovan did not forget his roots. He paid Timothy’s early bills in setting up his practice in Buffalo after he graduated from Columbia’s medical school and covered Vincent’s education expenses at the Dominican House of Studies. (Vincent, not Will, would be the priest in the family.) But his generosity was not without strings—big brother soon became preachy about how his siblings were so freely spending his dollars. Seminary students who swear oaths of poverty tend “to forget the significance of money,” he wrote to Vincent in one of many nagging letters. “It doesn’t grow on trees.” And “don’t get too self-righteous,” he added in the note. Donovan sent his sister, Loretta, an allowance to attend Immaculata Seminary in Washington, D.C., but he had the seminary’s sisters send him Loretta’s grades and they were “horrible,” he complained: Fs in Latin and geometry, a D in music harmony.

In the spring of 1912, Donovan began a major diversion. He and a group of young professionals and businessmen, many of them Saturn Club members, organized their own Army National Guard cavalry unit, called Troop I. It started out more as a drill, riding, and camping club for well-to-do city boys, most of whom, like Donovan, had never marched in a line, mounted a horse, or slept outside. They soon became known as the “Silk Stocking Boys”—and even Donovan found his comrades at first to be a provincial collection of military neophytes.

Drilling every Friday night, the “Business Men’s Troop” (the nickname they preferred instead of the Silk Stocking Boys) was an egalitarian bunch. They wrote bylaws for their organization (officers wore uniforms to drills while enlisted men did not have to) and elected their own leaders. Donovan was made captain of the troop. He took his command seriously, buying dozens of books on military strategy and attending Army classes two nights a week on combat tactics. Despite grousing from the men because they had to buy their own horses and equipment, Troop I soon became a popular Buffalo pastime for adventurous spirits. In four years, it had a hundred cavalrymen in uniform with another thirty-six being trained and a waiting list of more wanting to join.

AS HIS FORTUNES rose in Buffalo, Donovan also developed a reputation as a man with an eye for the ladies—though in polite company that kind of talk was always whispered. Privately, Donovan thought prostitution served a useful function for young hormone-charged men—although he never bought sex because he didn’t have to. He was considered one of Buffalo’s most eligible bachelors and had young women swooning over him, sometimes married ones. One of them was Eleanor Robson, a glamorous, English-born star of the New York City stage who had met Donovan (three years her junior) when he was a law student at Columbia and found that in addition to being an exciting romantic partner he also had acting talent. After Donovan returned to Buffalo, he continued to make occasional trips to New York for more drama coaching from Eleanor. But tongues started wagging in Buffalo when the private lessons continued after the thirty-year-old actress married August Belmont, a wealthy fifty-seven-year-old widower, in 1910. Between train rides to New York, Donovan in 1914 also met a smart, sophisticated, and fashionable blonde from one of Buffalo’s wealthiest families at the city’s Studio Club, where both were acting in amateur productions.

Her name was Ruth Rumsey. She was the daughter of Dexter Phelps Rumsey, a multimillionaire who had operated several Buffalo tanneries and leather stores, plowed his profits into real estate, and built a grand mansion on fashionable Delaware Avenue. Ruth, who was born in 1891 when Rumsey was sixty-four, was sent to Rosemary Hall, an exclusive boarding school in Greenwich, Connecticut, where she performed better in field hockey and class plays than in dreary subjects such as Latin and algebra. She was quick-witted, fast to assimilate facts, and not shy about speaking her mind around boyfriends. She spent summers traveling the world—Europe, Asia, the Middle East—and always first class. Back home she hunted foxes in Geneseo, sailed on the Great Lakes, and rode horses as well as any man. And when Dexter Rumsey died in 1906, the estate he left would one day make Ruth a millionaire.

Ruth’s mother, Susan, who was thirty years younger than her husband and herself a beautiful socialite and political activist on behalf of women’s suffrage, was not pleased with her daughter’s interest in this handsome young lawyer. Susan was an enlightened woman who had opened her home to artists and liberal causes since Dexter died, but Donovan had strikes against him. He was Irish Catholic for starters (even Ruth had a schoolgirl prejudice against Catholics) and he came from First Ward, not Delaware Avenue, despite his respectable bank account. Friends also had passed on to Susan the rumors that he played around—and was continuing to do so while he dated her daughter.

But Ruth had always been adventurous. Many rich girls of Buffalo found the tough, wild Irish boys of First Ward alluring. And one like Donovan—who had been a college football star, attended a prestigious law school, and was heart-thumping handsome—that kind of man proved irresistible. Ruth quickly fell in love with him and Donovan was smitten with her. During their first dates, “my heart was in my mouth,” he told her later. “I wanted you so much and yet thought you would choose someone of your own class.”

Ruth heard the rumors about other women in Donovan’s life, about the acting lessons he was taking from an old flame in New York, and she didn’t like them. The Robson affair came to a head one evening at a soirée the All Arts Club of Buffalo organized after Ruth’s and Bill’s engagement had been announced. Eleanor, who was in town visiting friends, performed Robert Browning’s poetic play In a Balcony for guests at Mrs. Hoyt’s new house on Amherst Road. Her leading man for the show was Donovan. Ruth leaned against a wall behind the audience silently steaming with jealousy. A column in the society page later made note of the “gala performance” and the fact that the young lawyer had been on the stage with the famous actress, which sparked more gossip in Buffalo. Afterward, Ruth delivered Donovan an ultimatum: Choose her or the acting lessons. Donovan chose his fiancée.

Bill and Ruth were married late Wednesday afternoon, July 15, 1914, in the conservatory of the Rumsey mansion. Fewer than a dozen friends and relatives attended the quiet, low-key ceremony—a signal to the rest of social Buffalo that Susan was not completely sold on this union. Donovan, however, soon won over his mother-in-law, who found him to be conscientious and hardworking. By the end of 1914, he was serving as her personal attorney for financial matters. When they returned from their honeymoon Ruth and Bill bought a comfortable home on Cathedral Parkway with money from Ruth’s trust. Susan bought them a car.

Donovan had definite ideas about marriage. Love was a reason to marry, but also a reason not to, he thought. A man and woman must be compatible in their interests, but there must also be “strong degrees of independence between them,” he told a friend. He thought he and Ruth were compatible and he hoped she would not be the clinging type. Most important, a man must find an unselfish woman, one not interested in dominating him. Donovan had no qualms about using Ruth’s money and social standing to get ahead. A man should not marry a woman because she is wealthy, he believed, but he should not refuse to marry a woman because she has money. A wife is an important asset and wealth does not make her any less important. He also continued to be a flirt. To a law firm colleague about to be married he advised: “Don’t give up your women friends. They’ll tend to improve your manners.”

THE STATE DEPARTMENT cable reached Donovan toward the end of June 1916, while he was in Berlin. Five months earlier the Rockefeller Foundation had commissioned him to be one of its representatives in Europe convincing two belligerents, Great Britain and Germany, to allow the foundation’s War Relief Commission to ship $1 million worth of food and clothing into famine-plagued Belgium, Serbia, and Poland. The position paid only expenses, but Donovan, who had grown increasingly interested in news stories he read about the European War, jumped at the chance to tour the continent and its battlefields, and, perhaps, scout future overseas clients for his law firm. But now Troop I had been ordered to the Texas border to join General John “Black Jack” Pershing’s expeditionary army hunting revolutionary leader Pancho Villa and his band attacking Americans across the border.

Donovan took the first ocean steamer he could book in July and sailed back to the United States to join his unit being deployed to McAllen, Texas. Ruth, who had been home alone caring for their firstborn for almost four months, was not happy her husband would be absent months more. The baby had arrived July 7, 1915. Instead of an Irish name, Donovan wanted a biblical one for his son, so they called him David. But Donovan had left when David was just eight months old and Ruth soon became overwhelmed caring for an infant and managing a house, where appliances always seemed to be breaking. Now David had just turned one year old and he had barely seen his father.

Troop I arrived at McAllen, a border town at the southern tip of Texas just north of the Rio Grande River, toward the end of July 1916. It was miserable duty, with temperatures soaring past 100 degrees during the day and Gulf storms turning their chigger-infested camp into a muddy swamp. Soon promoted to major, Donovan drilled his men relentlessly to toughen them, but they ended up battling the elements more than the Mexicans.

As fall stretched into winter, lonely Ruth began to suffer bouts of depression in Buffalo, which made her physically ill. Donovan thought she was being a hypochondriac and his response was harsh. In one early October letter he threatened to stop writing her if she did not start sending him cheery love notes. She should take a vacation “and not ‘mope’ around any longer,” he wrote. “You need to be in very good condition when your husband gets there,” he lectured in another note. “You had better make up your mind to get well.”

Troop I finally returned to Buffalo in March 1917, but Donovan remained with Ruth only long enough to make her pregnant again. His career once more took priority over family. He joined the 69th “Irish” Regiment of New York City to train for the war he was sure the United States would enter in Europe. The regiment, parts of which traced its lineage to the Revolutionary War, had more than three thousand of New York’s finest Irish sons, including the critically acclaimed poet Joyce Kilmer. They wanted Irish American officers to lead them in battle—no one more so than their chaplain, Francis Duffy, a liberal Catholic priest from a Bronx parish who recruited Donovan to head the regiment’s 1st Battalion with visions of him one day commanding the entire 69th. Donovan, who shared that ambition, came to worship the lanky chaplain with the gaunt face, who was devoted to the spiritual welfare of his soldiers.

In August, the 69th moved to Camp Mills on Long Island to begin training for war. It was redesignated the 165th and became part of the 42nd Division with an up-and-coming regular Army major named Douglas MacArthur as its chief of staff. Donovan, who soon discovered his ragtag group was a long way from being fit for trench warfare, had his men run three miles each morning, then strip to the waist and fight one another barehanded to make them mean. It made him an unpopular but respected commander. “I hate Donovan’s guts but I would go anywhere with him,” said one bruised but loyal soldier.

On August 13, 1917, Ruth delivered a baby girl, whom they named Patricia. Father Duffy baptized her with water from his canteen and she was officially designated the Daughter of the Regiment. Desperately missing his wife and children, Donovan moved the family to a bungalow outside Camp Mills for his final months there. He was delighted that Ruth seemed to be coming out of her depression.

Late in October, Donovan’s battalion boarded a troop train for Montreal, where the Tunisian passenger liner awaited to take them to Europe. He did not expect to come back alive. “I am glad so glad that you are happy,” Donovan wrote Ruth in a poignant letter. “Dearest, the knowledge that we are both making sacrifices in a good cause will bring us closer.” His wife’s love “is what keeps me going. I cannot be depressed. I will not be downhearted.”

Although they did not realize it then, October 1917 was the last time they would be truly man and wife.

First Ward

SKIBBEREEN, a coastal town on the southern tip of Ireland in County Cork, had a reputation for producing cultured people, or so went the lore among county folk. Timothy O’Donovan, who had been born in 1828, fit that stereotype. Raised by his uncle, a parish priest, Timothy had become a church schoolmaster. It was too humble an occupation, however, for the Mahoney family, who owned a large tract of land in the northern part of Cork and who took a dim view of their daughter, Mary, spending so much time with a lowly teacher eight years her senior. But the Mahoneys could not stop Timothy and Mary from falling in love. Attending the wedding of another couple they decided they would do the same—immediately. They eloped that day.

Growing poverty in Ireland and the promise of opportunity in America were powerful lures for the O’Donovan newlyweds, as they were for millions of young Irish men and women. They landed in Canada in the late 1840s with money Mary’s father grudgingly had given them to resettle and made their way across the southern border to Buffalo in western New York.

A boomtown, Buffalo was fast becoming a major transshipment point in the country for Midwest grain, lumber, livestock, and other raw materials dropped off at its Lake Erie port, then moved east on the Erie Canal to Albany and on to the Eastern Seaboard. The O’Donovans, who soon dropped the “O” from their name, settled in southwest Buffalo’s First Ward, a rough, noisy, polluted, and clannish neighborhood cut off from the rest of the city by the Buffalo River, where several thousand Irish families packed into clapboard shanties along narrow unpaved streets. Timothy could walk to the grain mills along the river, where he found employment as a scooper shoveling grain out of the holds of ships for the mills. Scooping was considered a good job, which made Timothy enough money to feed Mary and the ten children she eventually bore. He became a teetotaling layman in one of First Ward’s Catholic churches and allowed his home to be used by local Fenians, a secret society dedicated to independence for the Irish Republic.

The Donovans’ fourth child, Timothy Jr., who was born in 1858, proved to be a rebellious son who often played hooky from school and defied his father’s pleas that he attend college and make something of himself. Instead, “Young Tim,” as he had been called at home, went to work for the railroad, becoming a respected superintendent at the yard near Michigan Avenue. At one point the Catholic bishop of Buffalo called on him to calm labor unrest at the docks, which Young Tim succeeded in doing. He continued to display an independent streak, becoming an active Republican in his ward, a rarity for Irish Americans of his day, who voted practically lockstep with the Democratic Party.

In 1882, Young Tim married Anna Letitia Lennon, a brown-haired Irish beauty the same age as he (twenty-four), who had been orphaned when she was ten. Her father, a watchman for a grain elevator, had fallen off a wharf and drowned in the Buffalo River. Her mother had died the year before from an epidemic sweeping through First Ward. Anna had gone to live with cousins in Kansas City, but returned to Buffalo by the time she was eighteen, now a mature young woman with a love for fine literature.

To save money, the newlyweds went to live with the older Donovans at their 74 Michigan Avenue home; “Big Tim” (as the father was called) lived on the first floor with his family. Young Tim’s family took the second floor and the house’s enormous attic that had been converted into a dormitory. By then, Young Tim had come to regret profoundly that he had not studied in school and gone to college. He began to read widely, stocking hundreds of books in the library of the nicer two-story brick home he and Anna later bought outside of First Ward on Prospect Avenue. Tim also eventually left the rail yard to take a better job as secretary for the Holy Cross Cemetery. He and Anna became “lace curtain Irish,” the term the jealous “shanty Irish” of First Ward used for families that moved up and out. By the time he was middle-aged, Tim and his family were even listed in the Buffalo Blue Book for the city’s prominent—no small feat considering that as a young man looking for work he saw signs hanging from many businesses that read “No Irish Need Apply.”

It was while they were living with his father that Tim and Anna had their first child, whom they named William Donovan. He was born on New Year’s Day, 1883, at the Michigan Avenue home, delivered by a doctor who made a house call. Mary chose “William,” which was not a family name. The young boy picked his own middle name, “Joseph,” later at his confirmation. His parents called him “Will.”

Anna had another boy, Timothy, the next year and Mary was born in 1886. Disease killed the next four children shortly after birth or in the case of one, James, when he was four months shy of his fourth birthday. Vincent arrived by the time Will was eight and Loretta (her siblings called her “Loret”) came when the family had moved to Prospect Avenue and Will was fifteen.

From Anna’s side of the family came style and etiquette and the dreams of poets. From Tim came toughness and duty and honor to country and clan. At night the parents would read to Will and the other children from their books—Will’s favorites were the rich, nationalistic verses of Irish poet James Mangan. Saturday nights, when the workweek was done, Tim would often take the three boys with him to the corner saloon (practically every corner of First Ward had a saloon) to listen to the men argue about the Old Country and sing Irish ballads. Fights often broke out; a young man who walked into a First Ward pub always looked for the exit in case he had to get out fast. Tim, who like his father abstained from alcohol and also tobacco, sipped a ginger ale while Will and his brothers snitched sandwiches piled high on the bar.

Will adored his mother and tried to control his violent temper for her sake. But there was an intensity to the oldest Donovan son; he rarely smiled and fought often with other boys in the neighborhood (who could never make him cry) or with his brothers, who tended to be milder mannered. Tim, who could be hotheaded at times himself, finally bought boxing gloves and set up a ring in the backyard to let the three boys punch until they wore themselves out.

Both parents were stern disciplinarians and insisted that their children have proper schooling. When he was old enough to start, Will awoke early each morning and spent an hour taking the streetcar and walking to Saint Mary’s Academy and Industrial Female School on Cleveland Avenue north of First Ward. The school, which became known as “Miss Nardin’s Academy” after its founder, Ernestine Nardin, offered classes for working women in the evening; during the day, boys and girls attended for free. Will, who attended the academy until he was twelve, proved to be an erratic student. His spelling grades were poor. He earned barely a C in geography. But the nuns who taught him found him unusually well read for a child his age with an almost insatiable appetite for books. He also was not shy about standing in front of the class and reading stories or orations.

At thirteen, Will enrolled at Saint Joseph’s Collegiate Institute, a Catholic high school downtown run by the Christian Brothers. Saint Joseph’s charged tuition but James Quigley, the six-foot-tall bishop of Buffalo, who knew the Donovan family well, paid Will’s fee from a diocese fund. The school stressed public speaking, debating, and athletic competition. Will Donovan thrived. He acted in school plays, won the Quigley Gold Medal one year for his oration titled “Independence Forever,” and improved his grades. He also played football for Saint Joseph’s and was scrappy and ferocious on the field.

In Irish Catholic families, it was assumed that one of the boys would enter the priesthood. Tim and Anna never even hinted at the notion with their sons, but Will expected he would be the one when he graduated from Saint Joseph’s in 1899. To make up his mind he enrolled in Niagara University, a Catholic college and seminary on the New York bank of the Niagara River separating the United States from Canada. The school was founded to “prepare young men for the fight against secularism and . . . indifference to religion,” as one university history put it.

Donovan, however, soon disabused himself of a religious calling as he plunged into his studies at Niagara. Father William Egan, a professor at the university who became another of Donovan’s religious mentors, gently advised him that he did not seem cut out for the cloth. Donovan also concluded “he wasn’t good enough to be a priest,” Vincent recalled. But for someone who had decided to take the secular road, Donovan still had a lot of fire and brimstone left in him. He won one oratorical contest with a speech titled “Religion—The Need of the Hour.” In florid prose he condemned anti-Christian forces corrupting the nation—a theme pleasing to the ears of the Vincentian fathers judging him. “We stand in the presence of these evils which threaten to overwhelm the world and hurl it into the abyss of moral degradation,” Donovan railed.

After three years of what amounted to prep school at Niagara, Father Egan convinced Donovan that the legal profession might be his calling (he certainly had the windpipes for the courtroom) and wrote him a glowing recommendation for Columbia College in New York City—which helped get him admitted in 1903 despite mediocre grades.

He continued to be an average student at Columbia, but the college gave him the opportunity to widen his intellectual horizon and explore ideas beyond Catholic dogma (though like Donovan, a large majority of his classmates professed to be conservative Republicans). At one point Donovan even questioned whether he wanted to remain in the Catholic Church and started attending services for other denominations and religions, including the Jewish faith, to check them out. He finally decided to stick with Catholicism.

Donovan soaked up campus life. He won the Silver Medal in a college oratory contest, rowed on the varsity crew squad, ran cross-country, and was the substitute quarterback for the college football team. Football elevated him to near campus-hero status by his senior year, when the coach let him in the game more often. (His gridiron career ended abruptly during the sixth game of the 1905 season when a Princeton lineman hobbled him with a tackle.) In the senior yearbook his classmates voted him the “most modest” and one of the “handsomest.”

Donovan was handsome, his dark brown hair brushed neatly to the side, his face angular but with soft features that showed manliness yet gentleness, and those captivating blue eyes. Young women found him irresistible and at Columbia Donovan began going out with them, gravitating toward girls with highbrow pedigrees. He dated Mary Harriman, a free spirit who attended nearby Barnard College and whose father was railroad tycoon Edward Henry Harriman. His most serious romance developed with Blanche Lopez, the stunningly beautiful daughter of Spanish aristocrats resettled in New York City, whom Donovan had met at a Catholic church near Columbia.

Donovan graduated with Columbia’s Class of 1905, earning a bachelor of arts degree. He immediately enrolled in Columbia Law School, which took him two years to complete. Donovan became a serious student. He caught the eye of Harlan Stone, a highly respected New York lawyer and academic who taught him equity law. Stone, who never looked at notes or raised his voice at students during class, was impressed by the kid from a rough Irish neighborhood, who asked and answered questions in such a thoughtful, measured tone. Stone was Donovan’s favorite professor—and over the years, a close friend.

One of Donovan’s classmates was Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The two never mingled, however, because they had absolutely nothing in common. Roosevelt came from a wealthy New York family, he had attended the country’s best schools (Groton, then Harvard), he was never particularly good at sports, he was not too serious a law student, and he was already married. Roosevelt saw Donovan on campus frequently but paid him no attention. Donovan, for his part, had no interest in the dandy from Hyde Park.

DONOVAN RETURNED to bustling Buffalo, worried that he had rushed through college and law school, that he wasn’t truly educated, not fully prepared for the courtroom. He moved back in with Tim and Anna at the Prospect Avenue house and seemed to them aimless at first. They were uncertain how their son, with all his fancy schooling, would now turn out. He mulled entering politics, an idea that horrified friends and relatives as a perfectly good waste of a fine education. After more than a year of indecision, Bill Donovan (only his parents and siblings still called him Will) finally joined the venerable law firm of Love & Keating on fashionable Ellicott Square in 1909, earning almost $1,800 a year as an associate—a respectable enough salary that guaranteed him the “promise of future success,” as one local newspaper noted. Two years later, Donovan struck out on his own, forming a law partnership with Bradley Goodyear, a Columbia classmate from a prominent Buffalo family. Setting up an office in the Marine Trust Building downtown, they specialized in civil cases, which ranged from defending automobile drivers and their insurance companies in lawsuits (their bread-and-butter work) to settling a dispute (in one case) among neighbors over the death of a dog. Donovan and Goodyear took on associates. Three years later they merged with a firm run by one of Buffalo’s most well-connected lawyers—John Lord O’Brian, who had advised President William Howard Taft and would have the ear of future presidents on intelligence and defense issues.

Goodyear and O’Brien opened doors for Donovan in Buffalo society and among the exclusive clubs and civic organizations, where more important business contacts were made and lucrative deals were hatched. Donovan was admitted to the Saturn Club on Delaware Avenue and to the Greater Buffalo Club, where the city’s millionaires hung out. He joined the sailing club, organized a tennis and squash club with Goodyear (a magnet for business contacts), bought property with his spare cash, ordered his suits from a tailor in New York City, and began donating to the local Republican committee (required for a businessman on his way up).

As he moved up in Buffalo society, Donovan did not forget his roots. He paid Timothy’s early bills in setting up his practice in Buffalo after he graduated from Columbia’s medical school and covered Vincent’s education expenses at the Dominican House of Studies. (Vincent, not Will, would be the priest in the family.) But his generosity was not without strings—big brother soon became preachy about how his siblings were so freely spending his dollars. Seminary students who swear oaths of poverty tend “to forget the significance of money,” he wrote to Vincent in one of many nagging letters. “It doesn’t grow on trees.” And “don’t get too self-righteous,” he added in the note. Donovan sent his sister, Loretta, an allowance to attend Immaculata Seminary in Washington, D.C., but he had the seminary’s sisters send him Loretta’s grades and they were “horrible,” he complained: Fs in Latin and geometry, a D in music harmony.

In the spring of 1912, Donovan began a major diversion. He and a group of young professionals and businessmen, many of them Saturn Club members, organized their own Army National Guard cavalry unit, called Troop I. It started out more as a drill, riding, and camping club for well-to-do city boys, most of whom, like Donovan, had never marched in a line, mounted a horse, or slept outside. They soon became known as the “Silk Stocking Boys”—and even Donovan found his comrades at first to be a provincial collection of military neophytes.

Drilling every Friday night, the “Business Men’s Troop” (the nickname they preferred instead of the Silk Stocking Boys) was an egalitarian bunch. They wrote bylaws for their organization (officers wore uniforms to drills while enlisted men did not have to) and elected their own leaders. Donovan was made captain of the troop. He took his command seriously, buying dozens of books on military strategy and attending Army classes two nights a week on combat tactics. Despite grousing from the men because they had to buy their own horses and equipment, Troop I soon became a popular Buffalo pastime for adventurous spirits. In four years, it had a hundred cavalrymen in uniform with another thirty-six being trained and a waiting list of more wanting to join.

AS HIS FORTUNES rose in Buffalo, Donovan also developed a reputation as a man with an eye for the ladies—though in polite company that kind of talk was always whispered. Privately, Donovan thought prostitution served a useful function for young hormone-charged men—although he never bought sex because he didn’t have to. He was considered one of Buffalo’s most eligible bachelors and had young women swooning over him, sometimes married ones. One of them was Eleanor Robson, a glamorous, English-born star of the New York City stage who had met Donovan (three years her junior) when he was a law student at Columbia and found that in addition to being an exciting romantic partner he also had acting talent. After Donovan returned to Buffalo, he continued to make occasional trips to New York for more drama coaching from Eleanor. But tongues started wagging in Buffalo when the private lessons continued after the thirty-year-old actress married August Belmont, a wealthy fifty-seven-year-old widower, in 1910. Between train rides to New York, Donovan in 1914 also met a smart, sophisticated, and fashionable blonde from one of Buffalo’s wealthiest families at the city’s Studio Club, where both were acting in amateur productions.

Her name was Ruth Rumsey. She was the daughter of Dexter Phelps Rumsey, a multimillionaire who had operated several Buffalo tanneries and leather stores, plowed his profits into real estate, and built a grand mansion on fashionable Delaware Avenue. Ruth, who was born in 1891 when Rumsey was sixty-four, was sent to Rosemary Hall, an exclusive boarding school in Greenwich, Connecticut, where she performed better in field hockey and class plays than in dreary subjects such as Latin and algebra. She was quick-witted, fast to assimilate facts, and not shy about speaking her mind around boyfriends. She spent summers traveling the world—Europe, Asia, the Middle East—and always first class. Back home she hunted foxes in Geneseo, sailed on the Great Lakes, and rode horses as well as any man. And when Dexter Rumsey died in 1906, the estate he left would one day make Ruth a millionaire.

Ruth’s mother, Susan, who was thirty years younger than her husband and herself a beautiful socialite and political activist on behalf of women’s suffrage, was not pleased with her daughter’s interest in this handsome young lawyer. Susan was an enlightened woman who had opened her home to artists and liberal causes since Dexter died, but Donovan had strikes against him. He was Irish Catholic for starters (even Ruth had a schoolgirl prejudice against Catholics) and he came from First Ward, not Delaware Avenue, despite his respectable bank account. Friends also had passed on to Susan the rumors that he played around—and was continuing to do so while he dated her daughter.

But Ruth had always been adventurous. Many rich girls of Buffalo found the tough, wild Irish boys of First Ward alluring. And one like Donovan—who had been a college football star, attended a prestigious law school, and was heart-thumping handsome—that kind of man proved irresistible. Ruth quickly fell in love with him and Donovan was smitten with her. During their first dates, “my heart was in my mouth,” he told her later. “I wanted you so much and yet thought you would choose someone of your own class.”

Ruth heard the rumors about other women in Donovan’s life, about the acting lessons he was taking from an old flame in New York, and she didn’t like them. The Robson affair came to a head one evening at a soirée the All Arts Club of Buffalo organized after Ruth’s and Bill’s engagement had been announced. Eleanor, who was in town visiting friends, performed Robert Browning’s poetic play In a Balcony for guests at Mrs. Hoyt’s new house on Amherst Road. Her leading man for the show was Donovan. Ruth leaned against a wall behind the audience silently steaming with jealousy. A column in the society page later made note of the “gala performance” and the fact that the young lawyer had been on the stage with the famous actress, which sparked more gossip in Buffalo. Afterward, Ruth delivered Donovan an ultimatum: Choose her or the acting lessons. Donovan chose his fiancée.

Bill and Ruth were married late Wednesday afternoon, July 15, 1914, in the conservatory of the Rumsey mansion. Fewer than a dozen friends and relatives attended the quiet, low-key ceremony—a signal to the rest of social Buffalo that Susan was not completely sold on this union. Donovan, however, soon won over his mother-in-law, who found him to be conscientious and hardworking. By the end of 1914, he was serving as her personal attorney for financial matters. When they returned from their honeymoon Ruth and Bill bought a comfortable home on Cathedral Parkway with money from Ruth’s trust. Susan bought them a car.

Donovan had definite ideas about marriage. Love was a reason to marry, but also a reason not to, he thought. A man and woman must be compatible in their interests, but there must also be “strong degrees of independence between them,” he told a friend. He thought he and Ruth were compatible and he hoped she would not be the clinging type. Most important, a man must find an unselfish woman, one not interested in dominating him. Donovan had no qualms about using Ruth’s money and social standing to get ahead. A man should not marry a woman because she is wealthy, he believed, but he should not refuse to marry a woman because she has money. A wife is an important asset and wealth does not make her any less important. He also continued to be a flirt. To a law firm colleague about to be married he advised: “Don’t give up your women friends. They’ll tend to improve your manners.”

THE STATE DEPARTMENT cable reached Donovan toward the end of June 1916, while he was in Berlin. Five months earlier the Rockefeller Foundation had commissioned him to be one of its representatives in Europe convincing two belligerents, Great Britain and Germany, to allow the foundation’s War Relief Commission to ship $1 million worth of food and clothing into famine-plagued Belgium, Serbia, and Poland. The position paid only expenses, but Donovan, who had grown increasingly interested in news stories he read about the European War, jumped at the chance to tour the continent and its battlefields, and, perhaps, scout future overseas clients for his law firm. But now Troop I had been ordered to the Texas border to join General John “Black Jack” Pershing’s expeditionary army hunting revolutionary leader Pancho Villa and his band attacking Americans across the border.

Donovan took the first ocean steamer he could book in July and sailed back to the United States to join his unit being deployed to McAllen, Texas. Ruth, who had been home alone caring for their firstborn for almost four months, was not happy her husband would be absent months more. The baby had arrived July 7, 1915. Instead of an Irish name, Donovan wanted a biblical one for his son, so they called him David. But Donovan had left when David was just eight months old and Ruth soon became overwhelmed caring for an infant and managing a house, where appliances always seemed to be breaking. Now David had just turned one year old and he had barely seen his father.

Troop I arrived at McAllen, a border town at the southern tip of Texas just north of the Rio Grande River, toward the end of July 1916. It was miserable duty, with temperatures soaring past 100 degrees during the day and Gulf storms turning their chigger-infested camp into a muddy swamp. Soon promoted to major, Donovan drilled his men relentlessly to toughen them, but they ended up battling the elements more than the Mexicans.

As fall stretched into winter, lonely Ruth began to suffer bouts of depression in Buffalo, which made her physically ill. Donovan thought she was being a hypochondriac and his response was harsh. In one early October letter he threatened to stop writing her if she did not start sending him cheery love notes. She should take a vacation “and not ‘mope’ around any longer,” he wrote. “You need to be in very good condition when your husband gets there,” he lectured in another note. “You had better make up your mind to get well.”

Troop I finally returned to Buffalo in March 1917, but Donovan remained with Ruth only long enough to make her pregnant again. His career once more took priority over family. He joined the 69th “Irish” Regiment of New York City to train for the war he was sure the United States would enter in Europe. The regiment, parts of which traced its lineage to the Revolutionary War, had more than three thousand of New York’s finest Irish sons, including the critically acclaimed poet Joyce Kilmer. They wanted Irish American officers to lead them in battle—no one more so than their chaplain, Francis Duffy, a liberal Catholic priest from a Bronx parish who recruited Donovan to head the regiment’s 1st Battalion with visions of him one day commanding the entire 69th. Donovan, who shared that ambition, came to worship the lanky chaplain with the gaunt face, who was devoted to the spiritual welfare of his soldiers.

In August, the 69th moved to Camp Mills on Long Island to begin training for war. It was redesignated the 165th and became part of the 42nd Division with an up-and-coming regular Army major named Douglas MacArthur as its chief of staff. Donovan, who soon discovered his ragtag group was a long way from being fit for trench warfare, had his men run three miles each morning, then strip to the waist and fight one another barehanded to make them mean. It made him an unpopular but respected commander. “I hate Donovan’s guts but I would go anywhere with him,” said one bruised but loyal soldier.

On August 13, 1917, Ruth delivered a baby girl, whom they named Patricia. Father Duffy baptized her with water from his canteen and she was officially designated the Daughter of the Regiment. Desperately missing his wife and children, Donovan moved the family to a bungalow outside Camp Mills for his final months there. He was delighted that Ruth seemed to be coming out of her depression.

Late in October, Donovan’s battalion boarded a troop train for Montreal, where the Tunisian passenger liner awaited to take them to Europe. He did not expect to come back alive. “I am glad so glad that you are happy,” Donovan wrote Ruth in a poignant letter. “Dearest, the knowledge that we are both making sacrifices in a good cause will bring us closer.” His wife’s love “is what keeps me going. I cannot be depressed. I will not be downhearted.”

Although they did not realize it then, October 1917 was the last time they would be truly man and wife.

Product Details

- Publisher: Free Press (February 21, 2012)

- Length: 480 pages

- ISBN13: 9781416576204

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Wild Bill Donovan Trade Paperback 9781416576204

- Author Photo (jpg): Douglas Waller Steve Wilson(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit