Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

The FastLife

Lose Weight, Stay Healthy, and Live Longer with the Simple Secrets of Intermittent Fasting and High-Intensity Training

By Dr Michael Mosley and Mimi Spencer

With Peta Bee

Table of Contents

About The Book

From Dr. Michael Mosley, the author of The 8-Week Blood Sugar Diet, comes a comprehensive volume combining the #1 New York Times bestseller The FastDiet and his results-driven high-intensity training program FastExercise for the ultimate one-stop health and wellness guide that helps you reinvent your body the Fast way!

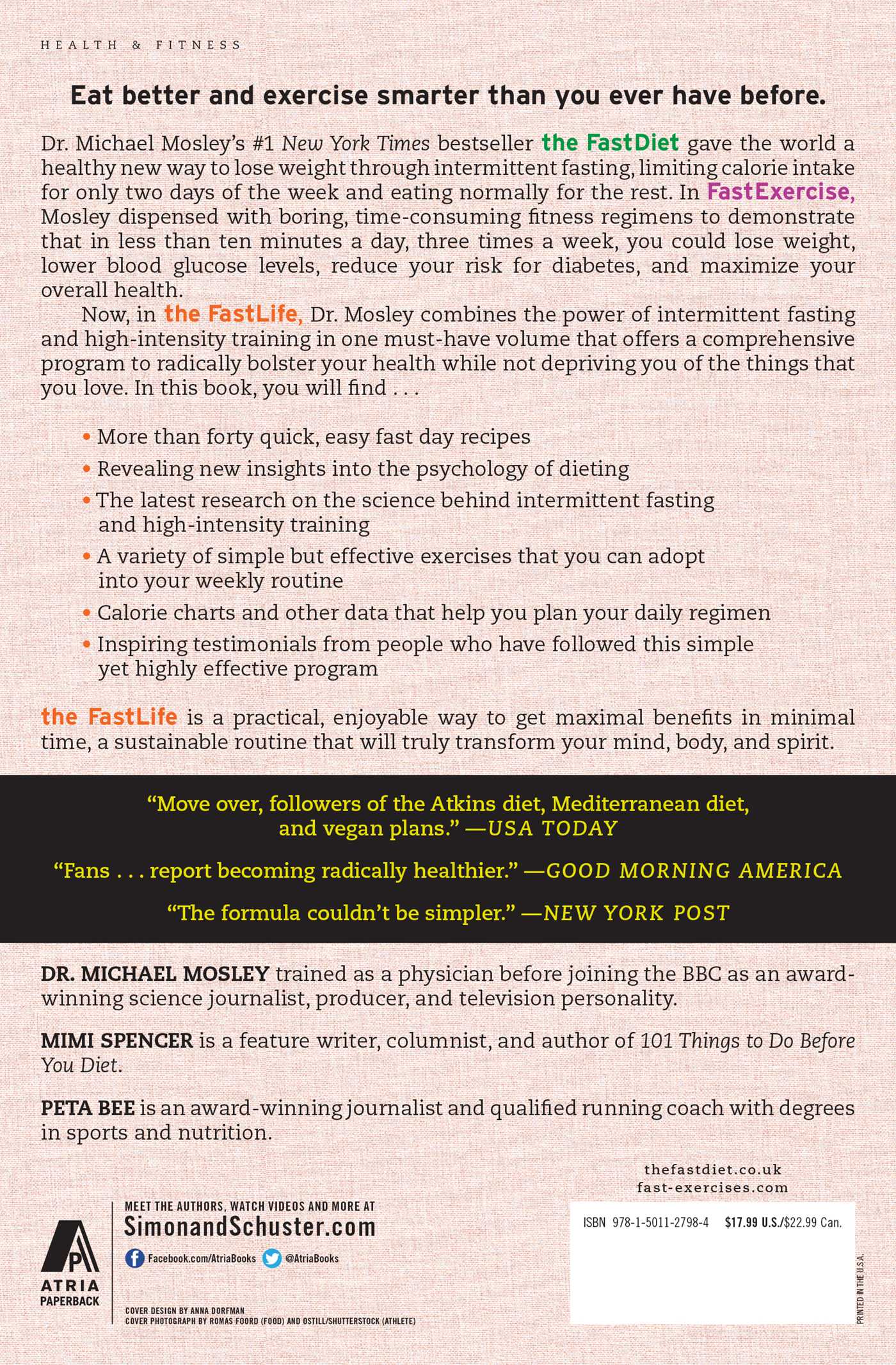

Eat better and exercise smarter than you ever have before.

Dr. Michael Mosley’s #1 New York Times bestseller The FastDiet gave the world a healthy new way to lose weight through intermittent fasting, limiting calorie intake for only two days of the week and eating normally for the rest. In FastExercise, Mosley dispensed with boring, time-consuming fitness regimens to demonstrate that in less than ten minutes a day, three times a week, you could lose weight, lower blood glucose levels, reduce your risk for diabetes, and maximize your overall health.

Now, in The FastLife, Dr. Mosley combines the power of intermittent fasting and high-intensity training in one must-have volume that offers a complete program to radically bolster your health while not depriving you of the things that you love. In this book, you will find:

-More than forty quick, easy fast day recipes

-Revealing new insights into the psychology of dieting

-The latest research on the science behind intermittent fasting and high-intensity training

-A variety of simple but effective exercises that you can adopt into your weekly routine

-Calorie charts and other data to help you plan your daily regimen

-Dozens of inspiring testimonials

The FastLife is a practical, enjoyable way to get maximal benefits in minimal time, a sustainable routine that will truly transform your mind, body, and spirit.

Eat better and exercise smarter than you ever have before.

Dr. Michael Mosley’s #1 New York Times bestseller The FastDiet gave the world a healthy new way to lose weight through intermittent fasting, limiting calorie intake for only two days of the week and eating normally for the rest. In FastExercise, Mosley dispensed with boring, time-consuming fitness regimens to demonstrate that in less than ten minutes a day, three times a week, you could lose weight, lower blood glucose levels, reduce your risk for diabetes, and maximize your overall health.

Now, in The FastLife, Dr. Mosley combines the power of intermittent fasting and high-intensity training in one must-have volume that offers a complete program to radically bolster your health while not depriving you of the things that you love. In this book, you will find:

-More than forty quick, easy fast day recipes

-Revealing new insights into the psychology of dieting

-The latest research on the science behind intermittent fasting and high-intensity training

-A variety of simple but effective exercises that you can adopt into your weekly routine

-Calorie charts and other data to help you plan your daily regimen

-Dozens of inspiring testimonials

The FastLife is a practical, enjoyable way to get maximal benefits in minimal time, a sustainable routine that will truly transform your mind, body, and spirit.

Excerpt

The FastLife CHAPTER ONE The Science of Fasting

FOR MOST ANIMALS OUT IN the wild, periods of feast or famine are the norm. Our remote ancestors did not often eat four or five times a day. Instead they would kill, gorge, lie around, and then have to go for long periods of time without having anything to eat. Our bodies and our genes were forged in an environment of scarcity, punctuated by the occasional massive blowout.

These days, of course, things are very different. We eat all the time. Fasting—the voluntary abstaining from eating food—is seen as a rather eccentric, not to mention unhealthy, thing to do. Most of us expect to eat at least three meals a day and have substantial snacks in between. In between the meals and the snacks, we also graze: a milky cappuccino here, the odd cookie there, or maybe a smoothie because it’s “healthier.”

Once upon a time, parents told their children, “Don’t eat between meals.” Those times are long gone. Recent research in the United States, which compared the eating habits of 28,000 children and 36,000 adults over the last thirty years, found that the amount of time between what the researchers coyly described as “eating occasions” has fallen by an average of an hour. In other words, over the last few decades the amount of time we spend “not eating” has dropped dramatically.1 In the 1970s, adults would go about four and a half hours without eating, while children would be expected to last about four hours between meals. Now it’s down to three and a half hours for adults and three hours for children, and that doesn’t include all the drinks and nibbles.

The idea that eating little and often is a “good thing” has been driven partly by snack manufacturers and faddish diet books, but it has also had support from the medical establishment. Their argument is that it is better to eat lots of small meals because that way we are less likely to get hungry and gorge on high-fat junk. I can appreciate the argument, and there have been some studies that suggest there are health benefits to eating small meals regularly, as long as you don’t simply end up eating more. Unfortunately, in the real world that’s exactly what happens.

In the study I quoted above, the authors found that compared to thirty years ago, we not only eat around 180 calories a day more in snacks—much of it in the form of milky drinks, smoothies, carbonated beverages—but we also eat more when it comes to our regular meals, up by an average of 120 calories a day. In other words, snacking doesn’t mean that we eat less at mealtimes; it just whets the appetite.

Do you need to eat lots of small meals to keep your metabolic rate high?

One of the other supposed benefits of eating lots of small meals is that it will increase your metabolic rate and help you lose weight. But is it true?

In a recent study, researchers at the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine in Prague decided to test this idea by feeding two groups of type 2 diabetics meals with the same number of calories, but taken as either two or six meals a day.2

Both groups ate 1,700 calories a day. The “two meals a day group” ate their first meal between 6:00 a.m. and 10:00 a.m. and their next meal between noon and 4:00 p.m. The “snackers” ate their 1,700 calories as 6 meals, spread out at regular intervals throughout the day. Despite eating the same number of calories, the “two meal a day” group lost, on average, 3 pounds more than the snackers and about 11/2 inches more around their waists.

Contrary to what you might expect, the volunteers eating their calories spread out as 6 meals a day felt less satisfied and hungrier than those sticking to the two meals. The lead scientist, Dr. Kahleova, believes cutting down to two meals a day could also help people without diabetes who are trying to lose weight.

So, simply cutting out snacks and one meal a day could be an effective weight-loss strategy. Yet eating throughout the day is now so normal, so much the expected thing to do, that it is almost shocking to suggest there is value in doing the absolute opposite. When I first started deliberately cutting back my calories two days a week, I discovered some unexpected things about myself, my beliefs, and my attitudes to food.

I discovered that I often eat when I don’t need to. I do it because the food is there, because I am afraid that I will get hungry later, or simply from habit.

I assumed that when you get hungry, it builds and builds until it becomes intolerable, and so you bury your face in a vat of ice cream. I found instead that hunger passes, and once you have been really hungry, you no longer fear it.

I thought that fasting would make me distractible, unable to concentrate. What I’ve discovered is that it sharpens my senses and my brain.

I wondered if I would feel faint for much of the time. It turns out the body is incredibly adaptable, and many athletes I’ve spoken to advocate training while fasting.

I feared it would be incredibly hard to do. It isn’t.

Why I Got Started

Although most of the great religions advocate fasting (the Sikhs are an exception, although they do allow fasting for medical reasons), I have always assumed that this was principally a way of testing yourself and your faith. I could see potential spiritual benefits, but I was deeply skeptical about the physical benefits.

I have also had a number of body-conscious friends who, down the years, have tried to get me to fast, but I could never accept their explanation that the reason for doing so was “to rest the liver” or “to remove the toxins.” Neither explanation made any sense to a medically trained skeptic like me. I remember one friend telling me that after a couple of weeks of fasting, his urine had turned black, proof that the toxins were leaving. I saw it as proof that he was an ignorant hippie and that whatever was going on inside his body as a result of fasting was extremely damaging.

As I wrote earlier, what convinced me to try fasting was a combination of my own personal circumstances—in my midfifties, with high blood sugar, slightly overweight—and the emerging scientific evidence, which I list below.

That Which Does Not Kill Us Makes Us Stronger

There were a number of researchers who inspired me in different ways, but one who stands out is Dr. Mark Mattson of the National Institute on Aging in Bethesda, Maryland. A few years ago he wrote an article with Edward Calabrese in New Scientist magazine. Entitled “When a little poison is good for you,”3 it really made me sit up and think.

“A little poison is good for you” is a colorful way of describing the theory of hormesis—the idea that when a human, or indeed any other creature, is exposed to a stress or toxin, it can toughen them up. Hormesis is not just a variant of “join the army and it will make a man of you”; it is now a well-accepted biological explanation of how things operate at the cellular level.

Take, for example, something as simple as exercise. When you run or pump iron, what you are actually doing is damaging your muscles, causing small tears and rips. If you don’t completely overdo it, then your body responds by doing repairs, making the muscles stronger in the process.

Thinking or having to make decisions can also be stressful, yet there is good evidence that challenging yourself intellectually is good for your brain, and the reason it is good is because it produces changes in brain cells that are similar to the changes you see in muscle cells after exercise. The right sort of stress keeps us younger and smarter.

Vegetables are another example of the power of hormesis. We all know that we should eat lots of fruits and vegetables because they are chock full of antioxidants—and antioxidants are great because they mop up the dangerous free radicals that roam our bodies doing harm.

The trouble with this widely accepted explanation of how fruit and vegetables “work” is that it is almost certainly wrong, or at least incomplete. The levels of antioxidants in fruits and vegetables are far too low to have the profound effects they clearly do. In addition, the attempts to extract antioxidants from plants and then give them to us in a concentrated form as a health-inducing supplement have been unconvincing when tested in long-term trials. Beta carotene, when you get it in the form of a carrot, is undoubtedly good for you. When beta carotene was taken out of the carrot and given as a supplement to patients with cancer, it actually seemed to make them worse.

If we look through the prism of hormesis at the way vegetables work in our bodies, we can see that the reasons for their benefits are quite different.

Consider this apparent paradox: Bitterness is often associated in the wild with poison, something to be avoided. Plants produce a huge range of so-called phytochemicals, and some of them act as natural pesticides to keep mammals like us from eating them. The fact that they taste bitter is a clear warning signal: “keep away.” So there are good evolutionary reasons why we should dislike and avoid bitter-tasting foods. Yet some of the vegetables that are particularly good for us, such as cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, and other members of the genus Brassica, are so bitter that even as adults many of us struggle to love them.

The resolution to this paradox is that these vegetables taste bitter because they contain chemicals that are potentially poisonous. The reason they don’t harm us is that these chemicals exist in vegetables at low doses that are not toxic. Instead they activate stress responses and switch on genes that protect and repair.

Once you start looking at the world in this way, you realize that many activities we initially find stressful—eating bitter vegetables, going for a run, intermittent fasting—are far from harmful. The challenge itself seems to be part of the benefit. The fact that prolonged starvation is clearly very bad for you does not imply that short periods of intermittent fasting must be a little bit bad for you. In fact the reverse is true.

This point was vividly made to me by Dr. Valter Longo, director of the University of Southern California’s Longevity Institute. His research is mainly into the study of why we age, particularly concerning approaches that reduce the risk of developing age-related diseases such as cancer and diabetes.

I went to see Valter, not just because he is a world expert, but also because he had kindly agreed to act as my fasting mentor and buddy, to help inspire and guide me through my first experience of fasting.

Valter has not only been studying fasting for many years, he is also a keen adherent of it. He lives by his research and thrives on the sort of low-protein, high-vegetable diet that his grandparents enjoy in southern Italy. Perhaps not coincidentally, his grandparents live in a part of Italy that has an extraordinarily high concentration of long-lived people.

As well as following a fairly strict diet, Valter skips lunch to keep his weight down. Beyond this, once every six months or so he does a prolonged fast that lasts several days. Tall, slim, energetic, and Italian, he is an inspiring poster boy for would-be fasters.

The main reason he is so enthusiastic about fasting is that his research, and that of others, has demonstrated the extraordinary range of measurable health benefits you get from doing it. Going without food for even quite short periods of time switches on a number of so-called repair genes, which, as he explained, can confer long-term benefits. “There is a lot of initial evidence to suggest that temporary periodic fasting can induce long-lasting changes that can be beneficial against aging and diseases,” he told me. “You take a person, you fast them, after twenty-four hours everything is revolutionized. And even if you took a cocktail of drugs, very potent drugs, you will never even get close to what fasting does. The beauty of fasting is that it’s all coordinated.”

Fasting and Longevity

Most of the early long-term studies on the benefits of fasting were done on rodents. They gave us important insights into the molecular mechanisms that underpin fasting.

In one early study from 1945, mice were fasted for either one day in four, one day in three, or one day in two. The researchers found that the fasted mice lived longer than a control group, and that the more they fasted, the longer they lived. They also found that unlike calorie-restricted mice, the fasted mice were not physically stunted.4

Since then, numerous studies have confirmed, at least in rodents, the value of fasting. Not only does fasting extend their lifespan, but it also increases their “healthspan,” the amount of time they live without chronic age-related diseases. Postmortems on rodents that have been calorie restricted show they have far fewer signs of cancer, heart disease, or neurodegeneration.

A recent article in the prestigious science journal Nature points to the wealth of research on the benefits of fasting, while at the same time noting sadly that so far “these insights have made hardly a dent in human medicine.”5 But why does fasting help? What is the mechanism?

Valter has access to his own supply of genetically engineered mice known as dwarf or Laron mice, which he was keen to show me. These mice, though small, hold the record for longevity extension in a mammal. In other words, they live for an astonishingly long time.

The average mouse doesn’t live that long, perhaps two years. Laron mice live nearly twice that, many for almost four years when they are also calorie restricted. In a human, that would be the equivalent of reaching almost 170.

The fascinating thing about Laron mice is not just how long they live, but that they stay healthy for most of their very long lives. They simply don’t seem to be prone to diabetes or cancer, and when they die, more often than not it is of natural causes. Valter told me that during an autopsy, it is often impossible to find a cause of death. The mice just seem to drop dead.

The reason these mice are so small and so long-lived is that they are genetically engineered so that their bodies do not respond to a hormone called IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1. IGF-1, as its name implies, has growth-promoting effects on almost every cell in the body. In other words, it keeps your cells constantly active. You need adequate levels of IGF-1 and other growth factors when you are young and growing, but high levels later in life appear to lead to accelerated aging and cancer. As Valter puts it, it’s like driving along with your foot flat down on the accelerator pedal, pushing the car to continue to perform all the time. “Imagine, instead of occasionally taking your car to the garage and changing parts and pieces, you simply kept on driving it and driving it and driving it. Well, the car, of course, is going to break down.”

Valter’s work is focused on trying to figure out how you can go on driving as much as possible, and as fast as possible, while enjoying life. He thinks the answer is periodic fasting. Because one of the ways fasting works is by making your body reduce the amount of IGF-1 it produces.

The evidence that IGF-1 plays a key role in many of the diseases of aging comes not just from engineered rodents like the Laron mice, but also from humans. For the last several years, Valter has been studying villagers in Ecuador with a genetic defect called Laron syndrome or Laron-type dwarfism. This is an extremely rare condition that affects fewer than 350 people in the entire world. People with Laron syndrome have a mutation in their growth hormone receptor (GHR) and very low levels of IGF-1. The genetically engineered Laron mice have a similar type of GHR mutation.

The villagers with Laron syndrome are normally quite short; many are less than four feet tall. The thing that is most surprising about them, however, is that like the Laron mice, they simply don’t seem to develop common diseases like diabetes and cancer. In fact, Valter says that though they have been studied for many years, he has not come across a single case of someone with Laron dying of cancer. Yet their relatives, who live in the same household but who don’t have Laron syndrome, do get cancer.

Disappointingly for anyone hoping that IGF-1 will provide the secrets of immortality, people with Laron syndrome—unlike the mice—are not that exceptionally long-lived. They certainly lead long lives, but not extremely long lives. Valter thinks one reason for this may be that they tend to enjoy life rather than worry about their lifestyle. “They smoke, eat a high-calorie diet, and then they look at me and they say, ‘Oh, it doesn’t matter, I’m immune.’?”

Valter thinks they prefer the idea of living as they want and dying at age 85, rather than living more carefully and perhaps going beyond 100. He would like to persuade some of them to take on a healthier lifestyle and see what happens, but knows he wouldn’t live long enough to see the outcome.

Fasting and Repair Genes

As well as reducing circulating levels of IGF-1, fasting also appears to switch on a number of repair genes. The reason this happens is not fully understood, but the evolutionary argument goes something like this: As long as we have plenty of food, our bodies are mainly interested in growing, having sex, and reproducing. Nature has no long-term plans for us; she does not invest in our old age. Once we’ve reproduced, we become disposable. So what happens if you decide to fast? Well, the body’s initial reaction is one of shock. Signals go to the brain reminding you that you are hungry, urging you to go out and find something to eat. But you resist. The body now decides that the reason you are not eating as much and as frequently as you usually do must be because you are now in a famine situation. In the past this would have been quite normal.

In a famine situation, there is no point in expending energy on growth or sex. Instead, the wisest thing the body can do is to spend its precious store of energy on repair, trying to keep you in reasonable shape until the good times return once more. The result is that as well as removing its foot from the accelerator, your body takes itself along to the cellular equivalent of a garage. There, all the little gene mechanics are ordered to start doing some of the urgent maintenance tasks that have been put off till now.

One of the things that calorie restriction does, for example, is to switch on a process called autophagy.6 Autophagy, meaning “self-eat,” is a process by which the body breaks down and recycles old and tired cells. Just as with a car, it is important to get rid of damaged or aging parts if you are going to keep things in good working order.

Intermittent Fasting and Stem Cell Regeneration

Fasting not only helps clear out damaged old cells but can also spark the production of new ones. In a particularly fascinating study published in June 2014, Valter and his colleagues showed, for the first time, that fasting can switch on stem cells and regenerate the immune system.7

Stem cells are cells that, when activated, can grow into almost any other cell. They can become brain, liver, heart tissue, whatever. The reason that this recent study is so exciting is because one of the things that happens when you age is that your immune system tends to get weaker. Being able to create new white cells and a more powerful immune system will not only keep infections at bay but may also reduce your risk of developing cancer; mutating cells that could turn into a cancer are normally destroyed by the immune system long before they can escape and multiply.

There have been claims that fasting can harm your immune system and, initially, Valter’s studies seemed to support this view, as he explains, “When you starve, your system tries to save energy, and one of the things it can do to save energy is to recycle a lot of the immune cells that are not needed, especially those that may be damaged. What we started noticing in both our human work and animal work is that the white blood cell count goes down with prolonged fasting.”

Clearly in the long run this would be harmful, as a fall in white blood cells would make you more vulnerable to infections and to cancers. But, as we have seen with hormesis, just because something is bad for you when pushed to the extreme does not mean it is bad when done in moderation. Valter discovered, to his considerable surprise, that if you do a short fast and then eat, you get a rebound effect, with the creation of new, more active cells. “We could not have predicted,” he said, “that fasting would have such a remarkable effect.”

It seems that fasting not only clears out the old, damaged white blood cells and lowers levels of IGF-1, it also reduces the activity of a gene called PKA. PKA produces an enzyme that normally acts like a brake on regeneration. “PKA is the key gene that needs to be shut down in order for stem cells to switch into regenerative mode,” Valter says.

Intermittent fasting seems to give the “okay” for stem cells to go ahead and begin proliferating. This research certainly suggests that if your immune system is not as effective as it was (either because you are older or because you have had a medical treatment such as chemotherapy), then periods of intermittent fasting may help regenerate it.

Michael Experiences a Four-Day Fast

Valter thinks that the majority of people with a BMI over 25 would benefit from fasting, but he also thinks that if you plan to do it for more than a day, it should be done in a proper center. As he puts it, “A prolonged fast is an extreme intervention. If it’s done well, it can be very powerful in your favor. If it’s done improperly, it can be very powerful against you.” With a prolonged fast lasting several days, you also have a drop in blood pressure and some fairly profound metabolic reprogramming. Some people faint. It’s not common, but it happens.

As Valter pointed out, the first time you try fasting for a few days, it can be a bit of a struggle. “Our bodies are used to high levels of glucose and high levels of insulin, so it takes time to adapt. But then eventually it’s not that hard.”

I wasn’t keen to hear “eventually,” but by then I knew I would have to give it a go. It was a challenge, and one I thought I could win. Brain against stomach. No contest. I had recently had my IGF-1 levels measured, and they were high. Not super high, as he kindly put it, but at the top end of the range (see my data on page 64).

High levels of IGF-1 are associated with a range of cancers, among them prostate cancer, which troubled my father. Would a four-day fast change anything?

I had been warned that the first few days might be tough, but after that I would start feeling the effects of a rush of what Valter termed well-being chemicals. Even better, the next time I fasted would be easier, because my body and brain would have a memory of it and understand what it was I was going through.

Having decided that I would try an extended fast, my next decision was how harsh to make it. A number of different countries have a tradition of fasting. The Russians seem to prefer it tough. For them, a fast consists of nothing but water, cold showers, and exercise. The Germans, on the other hand, prefer their fasts to be considerably gentler. Go to a fasting clinic in Germany and you will probably be fed around 200 calories a day in comfortable surroundings.

I wanted to see results, so I went for a British compromise. I would eat 25 calories a day, no cold showers, and just try working normally.

So on a warm Monday evening I enjoyed my last meal, an extremely filling dinner of steak, fries, and salad, washed down with beer. I felt a certain trepidation as I realized that for the next four days I would be drinking nothing but water, sugarless black tea, and coffee, and eating one measly cup of low-calorie soup a day.

Despite what I’d been told and read, before I began my fast I secretly feared that hunger would grow and grow, gnawing away inside me until I finally gave in and ran amok in a cake shop. The first twenty-four hours were quite tough, just as Valter had predicted, but as he also predicted, things got better, not worse. Yes, there were hunger pangs, sometimes quite distracting, but if I kept busy they went away.

During the first twenty-four hours of a fast there are some very profound changes going on inside the body. Within a few hours, glucose circulating in the blood is consumed. If that’s not being replaced by food, then the body turns to glycogen, a stable form of glucose that is stored in the muscles and liver.

Only when that’s gone does it really switch on fat burning. What actually happens is that fatty acids are broken down in the liver, resulting in the production of something called ketone bodies. These ketone bodies are now used by the brain instead of glucose as a source of energy.

The first two days of a fast can be uncomfortable because your body and brain are having to cope with the switch from using glucose and glycogen as a fuel to using ketone bodies. The body is not used to them, so you can get headaches, though I didn’t. You may find it hard to sleep. I didn’t. The biggest problem I had with fasting is hard to put into words; it was sometimes just feeling “uncomfortable.” I can’t really describe it more accurately than that. I didn’t feel faint, I just felt out of place.

I did, occasionally, feel hungry, but most of the time I was surprisingly cheerful. By day three the feel-good hormones had come to my rescue.

By Friday, day four, I was almost disappointed that it was ending. Almost. Despite Valter’s warning that it would be unwise to gorge immediately upon breaking a fast, I got myself a plate of bacon and eggs and settled down to eat. After a few mouthfuls I was full. I really didn’t need any more and in fact skipped lunch.

That afternoon I had myself tested again and discovered I had lost just under three pounds of body weight, a significant portion of which was fat. I was also happy to see that my blood glucose levels had fallen substantially and that my IGF-1 levels, which had been right at the top end of the recommended range, had gone right down. In fact, they had almost halved. This was all good news. I had lost some fat, my blood results were looking good, and I had learned that I can control my hunger. Valter was extremely pleased with these changes, particularly the fall in IGF-1, which he said would significantly reduce my risk of cancer. But he also warned me that if I went back to my old lifestyle, these changes would not be permanent.

Valter’s research points toward the fact that high levels of protein, the amounts found in a typical Western diet, help keep IGF-1 levels high. I knew that there is protein in foods like meat and fish, but I was surprised there is so much in milk. I used to like drinking a skinny latte most mornings. I had the illusion that because it is made of skim milk, it is healthy. Unfortunately, though low in fat, a large latte comes in at around 11 grams of protein. The recommendation is that you stick to government guidelines, which can be found at websites like http://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/everyone/basics/protein.html. Recommended levels vary according to age and gender. They are around 46 grams of protein for women between 19 and 75, and 55 grams of protein for men between 19 and 75. I realized that the lattes would have to go.

Fasting and Weight Loss

I did the four-day fast, as described above, mainly because I was curious. I would not recommend it as a weight-loss regimen because it is completely unsustainable. Unless they combine it with vigorous exercise, people who go on prolonged fasts lose muscle as well as fat. Then, when they stop (as they must eventually do), the risk is they will pile the weight right back on.

Fortunately, less drastic, intermittent fasting, the subject of this book, leads to steady weight loss, which seems to be both sustainable and without muscle loss.

ADF, Alternate-Day Fasting

One of the most extensively studied forms of short-term fasting is alternate-day fasting. As its name implies, it means you eat no food, or relatively little food, every other day. Dr. Krista Varady of the University of Illinois at Chicago has done a lot of the more recent studies in this area.

Krista is slim, charming, and very amusing. We first met in an old-fashioned American diner, where I guiltily ate a burger and fries while Krista told me about the work she has been doing with human volunteers.8 The version of ADF she has been testing is one where on fast days volunteers are allowed 25 percent of their normal energy needs, so men are allowed around 600 calories a day; women, 500 calories a day. On her regimen they eat all their calories in one go, at lunch. On their feed days they are asked to consume 125 percent of their normal energy needs.

Krista has done a number of studies on ADF, and what surprised her is that, although they are allowed to, people don’t go crazy on their nonfast days. “I thought when I started running these trials that people would eat 175 percent the next day; they’d just fully compensate and wouldn’t lose any weight. But most people eat around 110 percent, just slightly over what they usually eat. I haven’t measured it yet, but I think it involves stomach size, how far that can expand out. Because eating almost twice the amount of food that you normally eat is actually pretty difficult. You can do it over time; people who are obese, their stomachs get bigger to accommodate, you know, 5,000 calories a day. But just to do it right off is actually pretty difficult.”

In her earlier studies, the subjects were asked to stick to a low-fat diet, but what Krista wanted to know was whether ADF would also work if her subjects were allowed to eat a typical American high-fat diet. So she asked thirty-three obese volunteers, most of them women, to go on ADF for eight weeks. Before starting, the volunteers were divided into two groups. One group was put on a low-fat diet, eating low-fat cheeses and dairy, very lean meats, and a lot of fruit and vegetables. The other group was allowed to eat high-fat lasagna, pizza, the sort of diet a typical American might consume. Americans consume somewhere between 35 and 45 percent fat in their diet.

As Krista explained, the results were unexpected. The researchers and the volunteers had assumed that the people on the low-fat diet would lose more weight than those on the high-fat diet. But if anything, it was the other way around. The volunteers on the high-fat diet lost an average of 12.32 pounds, while those on the low-fat diet lost 9.24 pounds. They both lost about 2¾ inches around their waists.

Krista thinks that the main reason this happened was compliance. The volunteers randomized to the high-fat diet were more likely to stick to it than those on the low-fat diet simply because they found it a lot more palatable. And it wasn’t just weight loss. Both groups saw impressive drops in LDL cholesterol (the bad cholesterol) and in blood pressure. This meant that they had reduced their risk of cardiovascular disease, of having a heart attack or stroke.

Krista doesn’t want to encourage people to binge on junk food. She would much rather that people on ADF increase their intake of fruit and vegetables. The trouble is, as she pointed out rather exasperatedly, doctors have been encouraging people to embrace a healthy lifestyle for decades, and not enough of us are doing it. She thinks dietitians should take into account what people actually do rather than what we would like them to do.

One other significant benefit of intermittent fasting is that you don’t seem to lose muscle, which you would on a normal calorie-restricted regimen. Krista herself is not sure why that is and wants to do further research.

The Two-Day Fast

If you want to lose weight fast, then ADF is an effective, scientifically proven way to do it. The problem with ADF, which is why I personally am not so keen on it, is that you have to do it every other day.

In my experience this can be socially inconvenient as well as emotionally demanding. There is no pattern to your week and other people, friends, and family, find it hard to keep track of when your fast and feed days are.

Unlike Krista’s subjects, I was not particularly overweight to start with, so I also worried about losing too much weight too rapidly. That is why, having tried ADF for a short while, I decided to cut back to fasting two days a week.

I now have my own experience of this to fall back on (see page 59), together with the experiences of thousands of others who have written to me over the last two years. But what trials have been done on two-day fasts in humans?

Dr. Michelle Harvie, a dietitian based at the Genesis Breast Cancer Prevention Centre at the Wythenshawe Hospital in Manchester, England, has done a number of studies assessing the effects of a two-day fast on female volunteers. In one study, she divided 115 women into three groups. One group was asked to stick to a 1,500-calorie Mediterranean diet, and was also encouraged to avoid high-fat foods and alcohol.9 Another group was asked to eat normally five days a week, but to eat a 650-calorie, low-carbohydrate diet on the other two days. A final group was asked to avoid carbohydrates for two days a week, but was otherwise not calorie restricted.

After three months, the women on the two-day diet had lost an average of 8.1 pounds of fat, which was almost twice as much as the full-time dieters, who had lost an average of just 4.4 pounds of fat. Insulin resistance had also improved significantly in the two-day diet groups (see more on insulin on page 47). Those who stuck with the two-day diet for six months lost an average of 17 pounds and 3 inches from their waists. Some lost over 45 pounds.

The focus of Michelle’s work is trying to reduce breast cancer risk through dietary interventions. Being obese and having high levels of insulin resistance are both risk factors. On the Genesis website (www.genesisuk.org), she points out that they have been studying intermittent fasting at the Genesis Breast Cancer Prevention Centre, University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust, for over eight years and that their research has shown that cutting down on your calories for two days a week gives the same benefits, possibly more, than by going on a normal calorie-restricted diet. “To date, our research has concluded that intermittent diets appear to be a safe, viable, alternative approach to weight loss and maintaining a lower weight, in comparison to daily dieting.”

Another, more recent study looked at the effects on mood of being on a two-day diet.10

In this study, from Malaysia, thirty-two healthy males with an average age of 60 were randomly allocated to either a Sunnah (Muslim) fast, which meant cutting their calories on a Monday and a Thursday, or to a control group. They were then followed for three months.

Their mood was assessed using something called “The Profile of Mood States” questionnaire. The researchers found that not only did the intermittent fasting group lose far more fat than the control group, but that they felt much better on it. The researchers found that those doing intermittent fasting reported “significant decreases in tension, anger, confusion, and total mood disturbance, and improvements in vigor.”

On an anecdotal level, I have heard very good things from those who have tried intermittent fasting. Many people find it surprisingly easy, others struggle, but generally things improve after the first couple of weeks. As one faster says, “I used to have mood swings as well as headaches; it does pass as you get used to this new way of eating. I found by week six it had become part of my routine.”

Is It Just Calories?

If you eat 500 or 600 calories two days a week and don’t significantly overcompensate during the rest of the week, then you will lose weight in a steady fashion.

I recently came across one particularly fascinating study suggesting that when you eat can be almost as important as what you eat.

In this study, scientists from the Salk Institute for Biological Studies took two groups of mice and fed them a high-fat diet.11 All the mice got exactly the same amount of food to eat, the only difference being that the mice in one group were allowed to eat whenever they wanted, nibbling away when they were in the mood, rather like we do, while the mice in the other group had to eat their food within an eight-hour time period. This meant that there were sixteen hours of the day in which they were, involuntarily, fasting.

After 100 days, there were some truly dramatic differences between the two groups of mice. The mice who nibbled away at their fatty food had developed high cholesterol and high blood glucose, and had liver damage. The mice that had been forced to fast for sixteen hours a day put on far less weight (28 percent less) and suffered much less liver damage, despite having eaten exactly the same amount and quality of food. They also had lower levels of chronic inflammation, which suggests they had reduced risk of a number of diseases including heart disease, cancer, stroke, and Alzheimer’s.

The Salk researchers’ explanation for this is that all the time you are eating, your insulin levels are elevated and your body is stuck in fat-storing mode (see the discussion of insulin on page 47). Only after a few hours of fasting is your body able to turn off the fat-storing and turn on the fat-burning mechanisms. So if you are a mouse and you are continually nibbling, your body will just continue making and storing fat, resulting in obesity and liver damage.

I think there is strong evidence that fasting offers multiple health benefits, as well as helping to achieve weight loss. I had been aware of some of these claims before I got really interested in fasting and, though initially skeptical, I was converted by the sheer weight of evidence.

But there was one area of study that was a complete surprise: research showing how fasting can improve mood and protect the brain from dementia and cognitive decline. This, for me, was something new, unexpected, and hugely exciting.

Fasting and the Brain

The brain, as Woody Allen once said, is my second favorite organ. I might even put it first, as without it nothing else would function. The brain, around three pounds of pinkish-grayish gunk with the consistency of tapioca, has been described as the most complex object in the known universe. It allows us to build, write poetry, dominate the planet, and even understand ourselves, something no other creature has succeeded in doing.

It is also an extremely efficient energy-saving machine, doing all that complicated thinking and making sure our bodies are functioning properly while using the same amount of energy as a 25-watt lightbulb. The fact that our brains are normally so flexible and adaptable makes it even more tragic when they go wrong. I am aware that as I get older my memory has become more fallible. I’ve compensated by using a range of memory tricks I’ve picked up over the years, but even so, I find myself occasionally struggling to remember names and dates. Far worse than this, however, is the fear that one day I may lose my mind entirely, perhaps developing some form of dementia. Obviously I want to preserve my brain in as good a shape as possible and for as long as possible. Fortunately fasting seems to offer significant protection.

The man I went to discuss my brain with was Mark Mattson.

Mark, a professor of neuroscience at the National Institute on Aging, is one of the most revered scientists in his field, the study of the aging brain. I find his work genuinely inspiring—suggesting, as it does, that fasting can help combat diseases like Alzheimer’s, dementia, and memory loss.

Although I could have taken a taxi to his office, I chose to walk. I’m a fan of walking. It not only burns calories, it also improves the mood, and it may also help you retain your memory. Normally, as we get older, our brain shrinks, but one study found that in regular walkers the hippocampus, the area of the brain essential for memory, actually expanded.12 Regular walkers have brains that in MRI scans look, on average, two years younger than the brains of those who are sedentary.

Mark, who studies Alzheimer’s, lost his own father to dementia. He told me that although it didn’t directly motivate him to go into this particular line of research—when he started his work on Alzheimer’s disease, his father had not yet been diagnosed—it did give him insight into the condition.

Alzheimer’s affects around 26 million people worldwide, and the problem will grow as the population ages. New approaches are desperately needed because the tragedy of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia is that once you’re diagnosed, it may be possible to delay, but not prevent, the inevitable deterioration. You are likely to get progressively worse to the point where you need constant care for many years. By the end, you may not even recognize the faces of those you once loved.

Can Fasting Make You Smarter?

Just as Valter Longo had, Mark took me off to see some mice. Like Valter’s mice, these were genetically engineered, but Mark’s mice had been modified to make them more vulnerable to Alzheimer’s. The mice I saw were in a maze that they had to navigate in order to find food. Some of the mice performed this task with relative ease; others got disorientated and confused. This task and others like it are designed to reveal signs that the mice are developing memory problems; a mouse that is struggling will quickly forget which arm of the maze it has already traveled down.

If put on a normal diet, the genetically engineered Alzheimer’s mice will quickly develop dementia. By the time they are a year old, the equivalent of middle age in humans, they normally have obvious learning and memory problems. The animals put on an intermittent fast, something Mark prefers to call “intermittent energy restriction,” often go for up to twenty months without any detectable signs of dementia.13 They only really start deteriorating toward the end of their lives. That’s the equivalent in a human of the difference between developing signs of Alzheimer’s at the age of 50 and the age of 80. I know which I would prefer.

Disturbingly, when these mice are put on a typical junk-food diet, they go downhill much earlier than even normally fed mice. “We put mice on a high-fat and high-fructose diet,” Mark said, “and that has a dramatic effect; the animals have an earlier onset of the learning and memory problems, more accumulation of amyloid, and more problems with finding their way in a maze test.”

In other words, junk food makes these mice fat and stupid.

One of the key changes that occurs in the brains of Mark’s fasting mice is increased production of a protein called brain-derived neurotrophic factor. BDNF has been shown to stimulate stem cells to turn into new nerve cells in the hippocampus. As I mentioned earlier, this is a part of the brain that is essential for normal learning and memory.

But why should the hippocampus grow in response to fasting? Mark points out that from an evolutionary perspective it makes sense. After all, the times when you need to be smart and on the ball are when there’s not a lot of food lying around. “If an animal is in an area where there’s limited food resources, it’s important that they are able to remember where food is, remember where hazards are, predators and so on. We think that people in the past who were able to respond to hunger with increased cognitive ability had a survival advantage.”

We don’t know for sure if humans grow new brain cells in response to fasting; to be absolutely certain, researchers would need to put volunteers on an intermittent fast and then kill them, take their brains out, and look for signs of new neural growth. It seems unlikely that many would volunteer for such a project. But researchers are doing a study in which volunteers fast and then MRI scans are used to see if the size of their hippocampi has changed over time.

As I mentioned above, these techniques have been used in humans to show that regular exercise, such as walking, increases the size of the hippocampus. Hopefully, similar studies will show that two days a week of intermittent fasting are good for learning and memory. On a purely anecdotal level, and using a sample size of one, it seems to work. Before starting the FastDiet, I did a sophisticated memory test online. Two months in I repeated the test, and my performance had, indeed, improved. If you are interested in doing something similar, then I suggest you go to cognitivefun.net/test/2. Let us know how it works out.

Fasting and Mood

One of the things that Valter Longo and others told me before I began my four-day fast was that it would be tough initially, but that after a while I would start to feel more cheerful, which was indeed what happened. Similarly, I was surprised to discover how positive I have felt while doing intermittent fasting. I expected to feel tired and crabby on my fasting days, but that didn’t happen at all. So is this improved mood simply a psychological effect—that people who do intermittent fasting and lose weight feel good about themselves—or are there also chemical changes that are influencing mood?

According to Mark Mattson, one of the reasons people may find intermittent fasting relatively easy to do is because of its effects on brain-derived neurotrophic factor. BDNF not only seems to protect the brain against the ravages of dementia and age-related mental decline, but it may also improve your mood.

There have been a number of studies going back many years that suggest rising levels of BDNF have an antidepressant effect; at least they do in rodents. In one study, researchers injected BDNF directly into the brains of rats and found this had similar effects to repeated use of a standard antidepressant.14 Another paper found that electroshock therapy, which is known to be effective in severe depression in human patients, seems to work, at least in part, because it stimulates the production of higher levels of BDNF.15

Mark Mattson believes that within a few weeks of starting a two-day-a-week fasting regimen, BDNF levels will start to rise, suppressing anxiety and elevating mood. He doesn’t currently have the human data to fully support this claim, but he is doing trials on volunteers in which, among other things, his team is collecting regular samples of cerebrospinal fluid (the liquid that bathes the brain and spinal cord) in order to measure the changes that occur during intermittent fasts. This is not a trial for the fainthearted, as it requires regular spinal taps, but as Mark pointed out to me, many of his volunteers are already undergoing early signs of cognitive change, so they are extremely motivated.

Mark is keen to study and promote the benefits of intermittent fasting, as he is genuinely worried about the likely effects of the current obesity epidemic on our brains and our society. He also thinks that if you are considering intermittent fasting, you should get going sooner rather than later: “The age-related cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease, the events that are occurring in the brain at the level of the nerve cells and the molecules in the nerve cells, those changes are occurring very early, probably decades before the subject starts to have learning and memory problems. That’s why it’s critical to start dietary regimens early on, when people are young or middle-aged, so that they can slow down the development of these processes in the brain and live to be ninety with their brain functioning perfectly well.”

Like Mark, I’m convinced the human brain benefits from short periods abstaining from food. This is an exciting and fast-emerging area of research that many will watch with great interest. Beyond the brain, though, intermittent fasting also has measurable, beneficial effects on other areas in the body—on the heart, on blood profile, on cancer risk. And that’s where we’ll turn now.

Fasting and the Heart

One of the main reasons I decided to try fasting was that I had tests suggesting I was heading for serious problems with my cardiovascular system. Nothing had happened yet, but the warning signs were flashing amber. The tests showed that my blood levels of LDL (low-density lipoprotein, the “bad” cholesterol) were disturbingly high, as were the levels of my fasting glucose.

To measure fasting glucose, you have to fast overnight, then give a sample of blood. The normal, desirable range is 3.9 to 5.8 mmol/l. Mine was 7.3 mmol/l. Diabetic, but not yet dangerously high. There are many reasons that you should do all you can to avoid becoming a diabetic, not the least the fact that it dramatically increases your risk of having a heart attack or stroke.

Fasting glucose is an important thing to measure because it is an indicator that all may not be well with your insulin levels.

Insulin: The Fat-Making Hormone

Insulin is a hormone that has a similar molecular structure to IGF-1, and like IGF-1 it tends to increase cell turnover and reduce autophagy (clearing up of old cells). But insulin is best known as a hormone that regulates blood sugar.

When we eat food, particularly foods rich in carbohydrates, our blood glucose levels rise and the pancreas, an organ tucked away below the ribs next to the left kidney, starts to churn out insulin. Glucose is the main fuel that our cells use for energy, but high levels of glucose circulating in the blood are toxic to your cells. The job of insulin, a hormone, is to regulate blood glucose levels, ensuring that they are neither too high nor too low. It normally does this with great precision. The problem comes when the pancreas gets overloaded.

Insulin is a sugar controller; it aids the extraction of glucose from blood and then stores it in places like your liver or muscles in a stable form called glycogen, to be used when and if it is needed. What is less commonly known is that insulin is also a fat controller. It inhibits something called lipolysis, the breakdown of stored body fat. At the same time, it forces fat cells to take up and store fat from your blood. Insulin makes you fat. High levels lead to increased fat storage, low levels to fat depletion.

The trouble with constantly eating lots of sugary, carbohydrate-rich foods and drinks, as we increasingly do, is that this requires the release of more and more insulin to deal with the glucose surge. Up to a point, your pancreas will cope by simply pumping out ever-larger quantities of insulin. This leads to greater fat deposition and also increases cancer risk. Naturally enough, this can’t go on forever. If you continue to produce ever-larger quantities of insulin, your cells will eventually rebel and become resistant to its effects. It’s rather like shouting at your children; you can keep escalating things, but after a certain point they will simply stop listening.

Eventually the cells stop responding to insulin; your blood glucose levels now stay permanently high, and you will find you have joined the 285 million people around the world who have type 2 diabetes, a massive and rapidly growing problem worldwide. Over the last twenty years, numbers have risen almost tenfold, and there is no obvious sign that this trend is slowing.

Diabetes is associated with an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, impotence, blindness, and amputation due to poor circulation. It is also associated with brain shrinkage and dementia. Not a pretty picture.

One way to prevent the downward spiral into diabetes is to do more exercise and eat foods that do not lead to such big spikes in blood glucose and that do not have such a dramatic effect on insulin levels. More on this later. The other way is to try intermittent fasting.

How Intermittent Fasting Affects Insulin Sensitivity and Diabetes

In a study published in 2005, eight healthy young men were asked to fast every other day, twenty hours a day, for two weeks.16 On their fasting days they were allowed to eat until 10:00 p.m., then not eat again until 6:00 p.m. the following evening. They were also asked to eat heartily the rest of the time to make sure they did not lose any weight.

The idea behind the experiment was to test the so-called thrifty hypothesis, the idea that since we evolved at a time of feast or famine, the best way to eat is to mimic those times. At the end of the two weeks, there were no changes in the volunteers’ weight or body fat composition, which is what the researchers had intended. There was, however, a big change in their insulin sensitivity. In other words, after just two weeks of intermittent fasting, the same amount of circulating insulin now had a much greater effect on the volunteers’ ability to store glucose or break down fat.

The researchers wrote jubilantly that “by subjecting healthy men to cycles of feast and famine we changed their metabolic status for the better.” They also added that “to our knowledge this is the first study in humans in which an increased insulin action on whole body glucose uptake and adipose tissue lipolysis has been obtained by means of intermittent fasting.”

One of the ways that intermittent fasting seems to improve insulin sensitivity is by forcing the body to break down fat cells and use the fat as an energy source. Researchers at the Intermountain Heart Institute in Utah reported at a recent meeting of the American Diabetes Association that after ten to twelve hours without food, the body starts looking for new energy sources. At the same time, it starts drawing LDL cholesterol from cells, possibly using it as fuel.

Dr. Benjamin Horne, director of the Institute, says that because fat cells are a major contributor to insulin resistance (when the body stops responding to insulin), breaking down fat cells may reduce the risk of diabetes developing. Short-term fasting also makes the cells of the body go into self-protection mode, where they become resensitized to insulin.

“Although fasting may protect against diabetes,” Dr. Horne cautions, “it’s important to keep in mind that these results are not instantaneous. It takes time. How long and how often people should fast for health benefits are additional questions we’re just beginning to examine.”

I don’t know what impact intermittent fasting has had on my insulin sensitivity—it’s a test that is hard to do and extremely expensive—but what I do know is that the effects on my blood sugar have been spectacular. Before I started intermittent fasting, my blood glucose level was 7.3 mmol/l, well above the acceptable range of 3.9 to 5.8 mmol/l. The last time I had my level measured it was 5.0 mmol/l, still a bit high but well within the normal range.

This is an incredibly impressive response. My doctor, who was preparing to put me on medication, was astonished at such a dramatic turnaround. Doctors routinely recommend a healthy diet to patients with high blood glucose, but it usually makes only a marginal difference. Intermittent fasting could have a game-changing effect on the nation’s health.

Fasting and Cancer

My father was a lovely man but not a particularly healthy one. Overweight for much of his life, by the time he reached his sixties he had developed not only diabetes but also prostate cancer. He had an operation to remove the prostate cancer, which left him with embarrassing urinary problems. Understandably, I am not at all keen to go down that road.

My four-day fast, under Valter Longo’s supervision, had shown me that it was possible to dramatically cut my IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) levels and by doing so, hopefully, my prostate cancer risk. I later discovered that by doing intermittent fasting and being a bit more careful with my protein intake, I could keep my IGF-1 down at healthy levels. The link between growth, fasting, and cancer is worth unpacking.

The cells in our bodies are constantly multiplying, replacing dead, worn out, or damaged tissue. This is fine as long as cellular growth is under control, but sometimes a cell mutates, grows uncontrollably, and turns into a cancer. Very high levels of a cellular stimulant like IGF-1 in the blood are likely to increase the chance of this happening.

When a cancer goes rogue, the normal options are surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation. Surgery is used to try to remove the tumor; chemotherapy and radiation are used to try to poison it. The major problem with chemotherapy and radiation is that they are not selective; as well as killing tumor cells they will also kill or damage surrounding healthy cells. They are particularly likely to damage rapidly dividing cells such as hair roots, which is why hair commonly falls out following therapy.

As I mentioned above, Valter Longo has shown that when we are deprived of food for even quite short periods of time, our body responds by slowing things down, going into repair and survival mode until food is once more abundant. That is true of normal cells. But cancer cells follow their own rules. They are, almost by definition, not under control and will go on selfishly proliferating whatever the circumstances. This “selfishness” creates an opportunity. At least in theory, if you fast just before chemotherapy, you create a situation in which your normal cells are hibernating while the cancer cells are running amok and are therefore more vulnerable.

In a paper published in 2008, Valter and colleagues showed that fasting “protects normal but not cancer cells against high-dose chemotherapy,”17 followed by another paper in which they showed that fasting increased the efficacy of chemotherapy drugs against a variety of cancers.18 Again, as is so often the case, this was a study done in mice. But the implications of Valter’s work were not missed by an eagle-eyed administrative judge named Nora Quinn, who saw a short article about it in the Los Angeles Times.

Nora’s Story

I met Nora in Los Angeles. She is a feisty woman with a terrific, dry sense of humor. Nora first noticed she had a problem when, one morning, she put her hand on her breast and felt a lump the size of a walnut under her skin. After indulging, as she put it, in the fantasy that it was a cyst, she went to the doctor; it was removed and sent to a pathologist.

“The reality of your life always comes out in pathology,” she told me. When the pathology report came back, it said that she had invasive breast cancer. She had a course of radiation and was about to start chemotherapy when she read about Valter’s work with mice.

She tried to speak to Valter, but he wouldn’t advise her because, up to that point, none of the trials he had run had been done with humans. He didn’t know if it was safe for someone about to undergo chemo to fast, and he certainly wasn’t going to encourage people like Nora to give it a go.

Undeterred, Nora did her own research and decided to try fasting for seven and a half days, before, during, and after her first bout of chemotherapy. Having discovered how tough it can be to do even a four-day fast while fully healthy, I’m surprised she was able to go through with it, though Nora says it’s not so hard and I’m just a wimp. The results were mixed.

“After the first chemo I didn’t get that sick, but my hair fell out, so I thought it wasn’t working.” So next time she didn’t fast, and she was only medium sick. “I thought, seven and a half days of fasting to avoid being medium sick, this is a really bad deal. I am so not doing that again.” So when it was time for her third course of chemo, she didn’t fast. That, she now feels, was a mistake. “I got sick. I don’t have words for how sick I was. I was weak, felt poisoned, and I couldn’t get up. I felt like I was moving through Jell-O. It was absolutely horrible.”

The cells that line the gut, like hair root cells, grow rapidly because they need to be constantly replaced. Chemotherapy can kill those cells, which is one reason that it can make people feel really ill.

By the time Nora had to undergo her fourth course of chemo, she had decided to try fasting once again. This time things went much better and she made a good recovery. She is currently cancer free.

Nora is convinced she benefited from fasting, but it’s hard to be sure because she wasn’t part of a proper medical trial. Valter and his colleagues at USC did, however, study what happened to her and ten other patients with cancer who had also decided to put themselves on a fast.19 All of them reported fewer and less severe symptoms after chemotherapy, and most of them, including Nora, saw improvements in their blood results. The white cells and platelets, for example, recovered more rapidly when they had chemo while they were fasting than when they did not.

But why did Nora go rogue? Why didn’t she fast under proper supervision? She says: “I decided to fast based on years of information from animal testing. I do agree that if you are going to do crazy things like I did, you should have medical supervision. But how? None of my doctors would listen to me.”

Nora’s self-experiment could have gone wrong, which is just one reason why such maverick behavior is not recommended. Her experience, however, and that of the other nine cancer patients, helped inspire further studies. For example, Valter and his colleagues have recently completed phase one of a clinical trial to see if fasting around the time of chemotherapy is safe—which it seems to be. The next phase is to assess whether it makes a measurable difference. At least ten other hospitals around the world are either doing or have agreed to do clinical trials. Go to our website, www.thefastdiet.co.uk, for the latest updates.

Fasting and Chronic Inflammation IF and Asthma

One of the other unexpected benefits of intermittent fasting is its effects on allergic diseases such as asthma and eczema. These are autoimmune diseases, the result of an overactive immune system that is mistakenly attacking the body’s own cells. You might imagine that if intermittent fasting leads to new, more active white blood cells then this in turn could make your asthma worse. Far from it. On our website several people have reported seeing improvements in their asthma since going on our diet.

DB, aged 44, went on the FastDiet and lost 14 pounds in a month, but more unexpectedly she also saw big improvements in her lung function. “I have changed nothing else at all, it can only be related to the FastDiet,” DB writes. As an experiment she decided to stop doing the diet for a while. “Guess what? My lung function tests have deteriorated significantly. Nothing else has changed. So for me that’s proof enough. I am back on the diet tomorrow.”

Unfortunately there has not been a lot of scientific research looking at whether intermittent fasting is genuinely helpful for asthma. A few years ago Professor Mark Mattson, of the National Institute on Aging, with Dr. James Johnson, did do a small pilot study of intermittent fasting with ten obese asthmatics (eight women and two men).20 The overweight asthmatics were put on an alternate-day fasting (ADF) diet for eight weeks. While on this diet they could eat what they wanted one day, then the following day they were asked to cut down to 20 percent of their normal calories. Nine of the ten volunteers managed to stick to the diet for the two months of the trial and actually reported feeling more energetic. They lost an impressive amount of weight, an average of 18 pounds, but what was more surprising is that within a couple of weeks of starting intermittent fasting their asthma symptoms also improved.

Other studies have shown that people who are overweight can experience improvements in their asthma if they lose a lot of weight (at least 13 percent of previous body weight), but the improvements they saw in this study started long before significant weight loss.

It seems something else was going on. The likeliest explanation is that ADF led to a big drop in inflammatory markers. Certain levels of tumor necrosis factor, a measure of chronic inflammation, fell dramatically over the course of the study. Since asthma is largely a disease of inflammation (inflamed airways make breathing harder), then anything that reduces the inflammation is likely to help.

IF and Eczema

Inflammation is also a characteristic feature of eczema (also known as dermatitis), an incredibly common skin condition. Eczema affects around 10 percent of people in Europe and the US. It can be mild, with occasional flare-ups when the skin becomes dry, scaly, and itchy. Or it can be severe, in which case you get weeping, crusting, and bleeding. My daughter had eczema when she was young and we had to battle constantly to stop her scratching. Fortunately, as with many children, the eczema disappeared when she hit her teens, but there is always the risk it will return. We have had a number of people contact us to say their eczema has unexpectedly improved once they started doing the FastDiet.

For example B wrote to say, “For several years I have had eight to ten mildly irritating small eczema patches on my arms and torso. Since I have been doing intermittent fasting, the patches are much, much milder and a few have just disappeared.”

Tracy also wrote about the improvements she’d seen: “The total disappearance of my eczema (I used to get quite irritating recurring patches between my fingers) was one of the earliest and happiest side effects of the lifestyle for me. My skin is a million times better in general but the eczema disappearance has made this well worth doing for that reason alone.”

Unfortunately I can’t find any recent studies on the impact of intermittent fasting on eczema, but if you have eczema and decide to give it a try, do let us know how it goes.

IF and Psoriasis

Psoriasis is an inflammatory skin condition where studies suggest that short periods of fasting may help. Psoriasis can look a lot like eczema. It normally consists of red or silvery, scaly patches that itch. It can appear as just a few patches or cover almost the entire body.

A review article recently published in the British Journal of Dermatology21 asked whether different diets made any difference.

Among the studies was one where twenty patients with arthritis and various skin diseases were put on a two-week modified fast, followed by a three-week vegetarian diet. Not everyone got better, but some patients experienced an improvement. The article concluded that “short-term fasting periods may improve severe symptoms.”

Certainly Annette, one of our followers at fastdiet.co.uk, thinks the FastDiet helped her psoriasis. She wrote to us to say: “I used to wake myself up scratching and sore. I started the 5:2 and within days, noticed an improvement. This has continued over the weeks to the point where I can now wear a skirt without tights, unthinkable before I started this diet.” Again, more research is badly needed.

Intermittent Fasting: My Personal Journey

As you’ve read, I started out by trying the four-day fast under Valter Longo’s supervision. But despite the improvements in my blood biochemistry and his obvious enthusiasm, I could not imagine doing lengthy fasts on a regular basis for the rest of my life. So, what next? Well, having met Krista Varady and learned all about ADF (alternate-day fasting) I decided to give that a go.

After a short while, however, I realized that it was just too tough physically, socially, and psychologically. It is undoubtedly an effective way to lose weight rapidly and to get powerful changes to your biochemistry, but it was not for me.

So I decided to try eating 600 calories, two days a week. It seemed a reasonable compromise and, more important, doable.

The 5:2 FastDiet is based on a number of different forms of intermittent fasting; it is not based on any one body of research, but is a synthesis.

Before embarking on the diet I decided to get myself properly tested, to see what effects it would have on my body. The following are the tests I did. Most are straightforward. The blood tests are, with one exception, tests your doctor should be happy to do for you.

Get on the Scale

The first and most obvious thing you will want to do is weigh yourself before embarking on this adventure. Initially, it is best to do this at the same time every day. First thing in the morning is, as I’m sure you know, when you will be at your lightest.

Ideally you should get a weighing machine that measures body fat percentage as well as weight, since what you really want to see is body fat levels fall. The cheaper machines are not fantastically reliable; they tend to underestimate the true figure, giving you a false sense of security. What they are quite good at doing, however, is measuring change. In other words, they might tell you when you start that you are 30 percent body fat when the true figure is closer to 33 percent. But they should be able to tell you when that number begins to fall.

Body Fat

Body fat is measured as a percentage of total weight. The machines you can buy do this by a system called impedance. There’s a small electric current that runs through your body; the machine measures the resistance. It does its estimation based on the fact that muscle and other tissues are better conductors of electricity than fat.

The way to get a truly accurate reading is with a machine called a DXA (formerly DEXA) scanner. It stands for “dual energy X-ray absorptiometry.” It is relatively expensive and far more reliable than, say, body mass index. Women tend to have more body fat than men. A man with a body fat percentage of more than 25 percent would be considered overweight. For a woman it would be 30 percent.

Calculate Your BMI

To calculate your body mass index, go to thefastdiet.co.uk where you can track your indices. This will not only do the calculation, but also tell you what it means.

Measure Your Stomach

BMI is useful, but it may not be the best predictor of future health. In a study of more than 45,000 women who were followed for sixteen years, the waist-to-height ratio was a superior predictor of who would develop heart disease.

The reason the waist matters so much is because the worst sort of fat is visceral fat, which collects inside the abdomen. This is the worst sort of distribution because it causes inflammation and puts you at much higher risk of diabetes. You don’t need fancy equipment to tell you if you have internal fat. All you need is a tape measure. Male or female, your waist should be less than half your height. Most people underestimate their waist size by about two inches because they rely on pant size. Instead, measure your waist by putting the tape measure around your belly button. Be honest. A definition of optimism is someone who steps on the scale while holding their breath. You are fooling no one.

Blood Tests

You should be able to get standard tests during a routine visit to your doctor.

Fasting Glucose

I chose to measure my fasting glucose because it is a really important measure of fitness even if you are not at risk of diabetes, and it’s a predictor of future health. Studies show that even moderately elevated levels of blood glucose are associated with increased risk of heart disease, stroke, and long-term cognitive problems. Ideally I would have had my insulin sensitivity measured, but that test is complex and expensive.

Cholesterol

They measure two types of cholesterol: LDL (low-density lipoprotein) and HDL (high-density lipoprotein). Broadly speaking, LDL carries cholesterol into the wall of your arteries while HDL carries it away. It is good to have a low-ish LDL and a high-ish HDL. One way you can express this is as a percentage of HDL to the sum of HDL plus LDL. Anything over 0.20 (20 percent) is good.

Triglycerides

These are a type of fat that is found in blood; they are one of the ways that the body stores calories. High levels are associated with increased risk of heart disease.

IGF-1

This is an expensive test and not available from every doctor. It is a measure of cell turnover and therefore of cancer risk. It may also be a marker for biological aging. I wanted to find out the effects of 5:2 fasting on my IGF-1. I had discovered that IGF-1 levels drop dramatically in response to a four-day fast, but after a month of normal eating they bounced right back to where they had been before.

My Data

These are the results of the physical measurements I took before starting the FastDiet.

ME

RECOMMENDED

HEIGHT

5'11" (71 inches)

WEIGHT

187 lbs.

BODY MASS INDEX

26.4

19–25

% OF BODY FAT

28%

Less than 25% for men

WAIST SIZE

36 "

Less than half your height

NECK SIZE

17 "

Less than 161/2"

I wasn’t obese, but both my BMI and my body fat percentage told me that I was overweight. I knew from doing an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan that much of my fat was collected internally, wrapping itself in thick layers around my liver and kidneys, disturbing all sorts of metabolic pathways.

Clearly, the fat wasn’t all inside my abdomen. Quite a bit had collected around my neck. This meant that I was snoring. Loudly. Neck size is a powerful predictor22 of whether you will snore or not. A neck size above 161/2 inches for men or 16 inches for women means you are in the danger zone.

MY RESULTS IN MMOL/L

RECOMMENDED

DIABETES RISK

FASTING GLUCOSE

7.3

3.9–5.8

HEART DISEASE FACTORS

TRIGLYCERIDES

HDL CHOLESTEROL

LDL CHOLESTEROL

1.4

1.8

5.5

Less than 2.3

0.9–1.5

Up to 3.0

HEART DISEASE RISK

HDL % OF TOTAL

23 %

20% and over

CANCER RISK

SOMATOMEDIN-C (IGF-1)

28.6 nmol/l

11.3–30.9 nmol/l

According to these data, my fasting glucose was worryingly high. I was a diabetic, so far only at the lower end of the range, but clearly heading toward trouble. My LDL was far too high, but I was to some extent protected by the fact that my triglycerides were low and my HDL high. This is not a good picture, though.

My IGF-1 levels were also too high, suggesting rapid turnover of cells and increased cancer risk.

After three months on the FastDiet there were some remarkable changes, as you’ll see in these charts.

ME

RECOMMENDED

HEIGHT

5' 11" (71 inches)

WEIGHT

168 lbs.

BODY MASS INDEX

24

19–25

% OF BODY FAT

21%

Less than 25% for men

WAIST SIZE

33"

Less than half your height

NECK SIZE

16"

Less than 161/2"

I had lost about 19 pounds, and my BMI and body fat percentage became respectable. I had to go out and buy smaller belts and tighter pants. I could fit into a dinner jacket I hadn’t worn for ten years. I had also stopped snoring, which delighted my wife and quite possibly the neighbors. Even better, my blood indicators had improved in a spectacular fashion.